Browse All Articles > Python illustrated (part 1)

The really strange introduction

Once upon a time there were individuals who intentionally put the grass seeds to the soil with anticipation of solving their nutrition problems. Or they maybe only played with seeds and noticed what happened... Some years later, people chew pizza made of flour, enjoying their holiday in Italy, thinking of nothing -- definitely not about the grass seeds that were put to the soil. Still, the local bakers strive for perfection in baking The Best Pizza in The World, choosing carefully the kind of flour.

Another time, another places, there were individuals that played with first computers. They knew everything about their computer -- till the last bit. (Frankly, it was a bit easier as there was not so much bits inside as they are now.) Often, they built the computer. Or at least they fell in love with it and knew how to build it (also in cases when they bought it), and they replayed in their imagination "how they are rebuilding the same", feeling themselves strong, self-confident in the area. They knew "much more" about "much less" in comparison with our present time.

"Keep the ballance." The greatly admired people are often extreme people. They often brought us something very valuable, but they were not understood in their time, and they often died poor or in physical or in mental sense. In other words, being odd makes it sometimes easier to be great in something. The question is whether you want that. On the other hand, focusing on being intentionally dumb in the chosen area to keep the statistic ballance inside the society and expecting to be automatically successful in the other areas... Well, it simply does not work.

"Why the hell is he writing such obvious things?" This is called a professional blindness. When focused on our professional problems, we often behave strangely. Programming is no exception. Experts often think about the users as about dumbs because the users cannot do such obvious things. And the pizza chewers complain like "Why the application is so complicated and still it does not do that one simple thing that I want?" And there are also people, who simply want to try programming to have some fun.

The very basic things should never be underestimated or postponed for learning later. It is no accident to call such things Basic Building Blocks of programming. You can put something that works when interconnecting several ready-to-be-used, bigger building blocks. However, it will not make you universal. This will not help you to approach any general problem that could be solved.

"One picture is worth of thousands word." Well, it depends. The truth is that "images" and "imagination" clearly have some common base. Good imaginagion is one of the key abilities of a successful programmer. In my opinion, this is the direction in which the beginners should be trained. Too many teachers are not aware of that. They may think that it is obvious and the students should already know that. The truth is that not all students are of that kind to naturally feel the same. Also, I may be wrong. Anyway, I am going to focuse on helping your imagination with images when explaining the basic building blocks of the Python programming language. The following serie (with at least one part ;) will show if the idea is good or not -- just react after reading the article.

"Stop writing when it is good enough. It will never be perfect." This is one of the golden rules. Another one says: "Never say never." A kind of paradox? Maybe. I will try to put both together. Based on your reactions to the specific parts, I will try to simplify or explain better the basics to that level (from different angles of view) that you will find nothing else to ask. (Just kidding. Everything can be improved.) If you like mathematical or otherwise formal approach to programming, you may not like the article. I will try to avoid mathematics and formalism -- not because I do not like it, but because beginners usually do not like it, and because it does not help to train in imagination if you have a poor one (no offense meant, no shame).

Objects

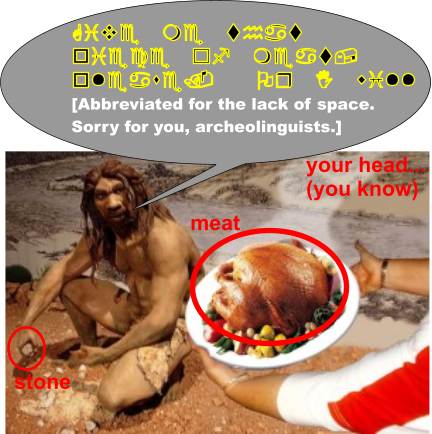

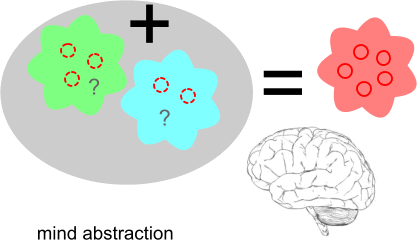

The reality does not need objects. It is our perception that tries to recognize the object. It is our brain that is not capable to capture the reality as collection of all recognizable and possibly interrelated details. Our brain needs simplification when thinking about complex things. The caveman's brain also needed that. What is tangible is more understandable. "Give me that piece of meat, please. Or I will hit your skull with that stone."

The reality does not need objects. It is our perception that tries to recognize the object. It is our brain that is not capable to capture the reality as collection of all recognizable and possibly interrelated details. Our brain needs simplification when thinking about complex things. The caveman's brain also needed that. What is tangible is more understandable. "Give me that piece of meat, please. Or I will hit your skull with that stone."

[My sorry for using and modifying the copyrighted image of the caveman diet (http://www.stayfitbug.com/

[My sorry for using and modifying the copyrighted image of the caveman diet (http://www.stayfitbug.com/Well, they are too complex and too distracting objects on the picture -- not good from a pedagogical point of view. And you are capable of abstract thinking, right?

Let's start with variables that are a kind of simplest version of objects in any programming language.

Variables

Even if you do not like the mathematical approach to programming, you should be aware of the fact that the name variables comes from mathematics. You know them from school as letters that are used to replace any number. You have learned how to search for their values if they were part of what we call equations. And you have learned how to manipulate symbolically the formulas so that you could get simpler formulas. To summarize, the variables in mathematics are used as symbolic replacements for the possible values.

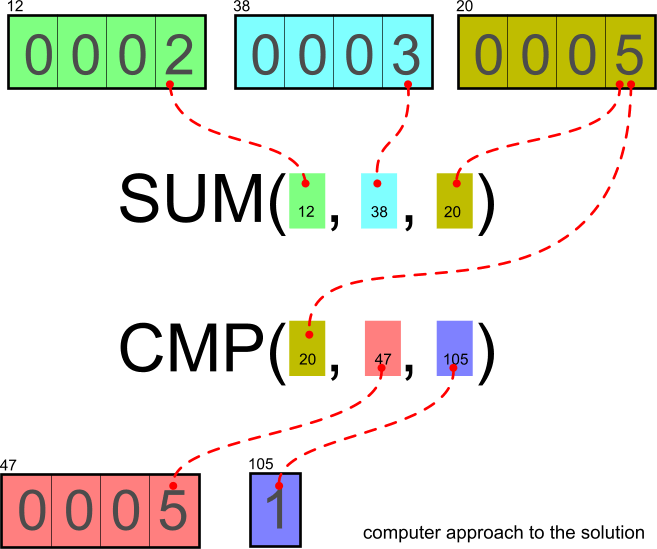

Now the computer-related point of view. Any value in computers need some memory space to be stored. One have to reserve certain amount of bytes -- the "bigger" value, the more bytes. So, from the hardware point of view, the variable is the memory space of some size placed somewhere. We have to know where the "where" is, and we (as humankind) decided to number the memory positions, and we name the numbers as the addresses. The hardware does not need any "names" for variables. The size and the placement in memory is all the processor needs to know when working with the content.

Now the computer-related point of view. Any value in computers need some memory space to be stored. One have to reserve certain amount of bytes -- the "bigger" value, the more bytes. So, from the hardware point of view, the variable is the memory space of some size placed somewhere. We have to know where the "where" is, and we (as humankind) decided to number the memory positions, and we name the numbers as the addresses. The hardware does not need any "names" for variables. The size and the placement in memory is all the processor needs to know when working with the content.

Humans are more error prone when working with numbers (unless the number means the sallary, or the pocket money, or the number of beers, or similar counting cases that are so obvious to know them right). When programming, we combine the mathematical thinking with the computer-related point of view. We think in terms of memory space, but we do not like to use the numeric address when thinking about the placement of that space. It would be too much details, and our brain would defend the situation using the "forget it" mechanism. The name for the space (instead of the numeric address) is much more acceptable. Our lazy brain likes abstractions. It does not like details, it likes working with fuzzy pictures generated by our imagination. The brain likes to search for the principles of the solution of the problem. When programming, we try to automatize the steps leading to the solution. Or we need to repeat the same steps many times in future (for a different input to get the wanted output), or we need to utilize the raw speed of the computer hardware and the ability to remember, to organize and to work with many boring details.

Humans are more error prone when working with numbers (unless the number means the sallary, or the pocket money, or the number of beers, or similar counting cases that are so obvious to know them right). When programming, we combine the mathematical thinking with the computer-related point of view. We think in terms of memory space, but we do not like to use the numeric address when thinking about the placement of that space. It would be too much details, and our brain would defend the situation using the "forget it" mechanism. The name for the space (instead of the numeric address) is much more acceptable. Our lazy brain likes abstractions. It does not like details, it likes working with fuzzy pictures generated by our imagination. The brain likes to search for the principles of the solution of the problem. When programming, we try to automatize the steps leading to the solution. Or we need to repeat the same steps many times in future (for a different input to get the wanted output), or we need to utilize the raw speed of the computer hardware and the ability to remember, to organize and to work with many boring details.

Programming languages are here to put the humans (who design the way to get the solution) and the computers together. A programming language is used for transformation of our abstract mental pictures of the solution to the form of a formal description of steps leading to the solution (for a computer). Having that function, our favourite programming language must be capable to describe the abstractions that were born in our brain. But also the reverse direction works: our favourite programming language uses constructions and data abstractions that form the abstract thinking. We gradually tend to use the programming-language abstractions as basic blocks for our imagination. In other words, we learn how to program in the programming language. This is one of the main reasons why we have to deeply understand the basic blocks of the programming language. We have to make the related abstract basic block for our thinking.

Programming languages are here to put the humans (who design the way to get the solution) and the computers together. A programming language is used for transformation of our abstract mental pictures of the solution to the form of a formal description of steps leading to the solution (for a computer). Having that function, our favourite programming language must be capable to describe the abstractions that were born in our brain. But also the reverse direction works: our favourite programming language uses constructions and data abstractions that form the abstract thinking. We gradually tend to use the programming-language abstractions as basic blocks for our imagination. In other words, we learn how to program in the programming language. This is one of the main reasons why we have to deeply understand the basic blocks of the programming language. We have to make the related abstract basic block for our thinking.

Back to variables. Let's agree that our mind picture and the programming language abstraction of a "variable" have the common features: 1) they can be represented by the name, 2) they are capable to store the value.

The programming languages introduced several ways how to put the name of the variable (called the identifier of the variable) with the related memory space. We use the variable names in our "program sources" which are basically text files that are later compiled somehow to something more acceptable by the computer hardware (to be executed as steps towards the solution).

Topics for the planned part 2

More about variables and about memory allocation:

- statically compiled languages

- statically allocated memory (compiled time)

- dynamically allocated memory (run time)

- dynamic languages

- directly bound (variable) name to the statically allocated memory

- indirectly bound name of a variable in compiled languages

- what is a pointer (explicit dereferencing)

- what is a reference

- type of a variable

- types, variables, and compiled languages

- types, variables, and scripting languages

- Python approach to types and variables (globals() -- dict of name->reference variables)

Have a question about something in this article? You can receive help directly from the article author. Sign up for a free trial to get started.

Comments (4)

Author

Commented:Commented:

2. You are presenting very abstract ideas which you haven't tied into Python

When I read a 'basics' article, I expect to see the central topic. I don't see any Python.

Commented:

I need to learn python so clicking on Pyton basics seemed to be a good start (EE articles are generally pretty good). This article seems to miss the python part. I'll have a look at 2 and 3.

Nice job taking the time to write an article though!

Author

Commented:Thanks for the reading and for the comment.