Browse All Articles > Python illustrated (part 2)

Less strange, but still introduction

This introduction was added (1st August, 2011) to reflect some reactions. Firstly, the term basics in the title of the article... As any other word, it is a symbol with meaning attached to the word by some agreement. Still, we always have to think in some context to understand the agreement. You may say that what is described in this and previous articles is not related to Python basics at all. It could be because you expect a text written in some context that you met when reading some other "basics". The article series could be renamed to Python foundation or Python internals. However, the later terms are more technical, and I do not think it would help you to understand what I want to write about. Instead, I am asking you to change the context of thinking about it. Tutorials often start with the simplest example that shows a working program (say "Hello, World!" -- it is also a kind of unspoken agreement bound to the "creation of a tutorial"). This is understandable. There are many ways of how to attract a beginner's attention. The context of "basics" in this series is based on "what you should know to understand". I am focusing on "mental pictures of what is done" rather than on "how to write the block of code". For that, I need also the text of this second part. I am aware of the situation that you may want to skip these two articles with disagreement. ("Not related to Python at all!") In the same time I believe, that the information will be useful for those who find some knowledge gaps when reading the next part 3.

The previous part 1 (http:A_5354-Python-basics-

For explaining principles of working with variables, we need some excursion outside the Python point of view. This part describes variables in context of traditional compiled languages to show some details. Let's talk about pointers and references. Good understanding will be necessary to swallow the part 3.

Variables in the (old) compiled languages

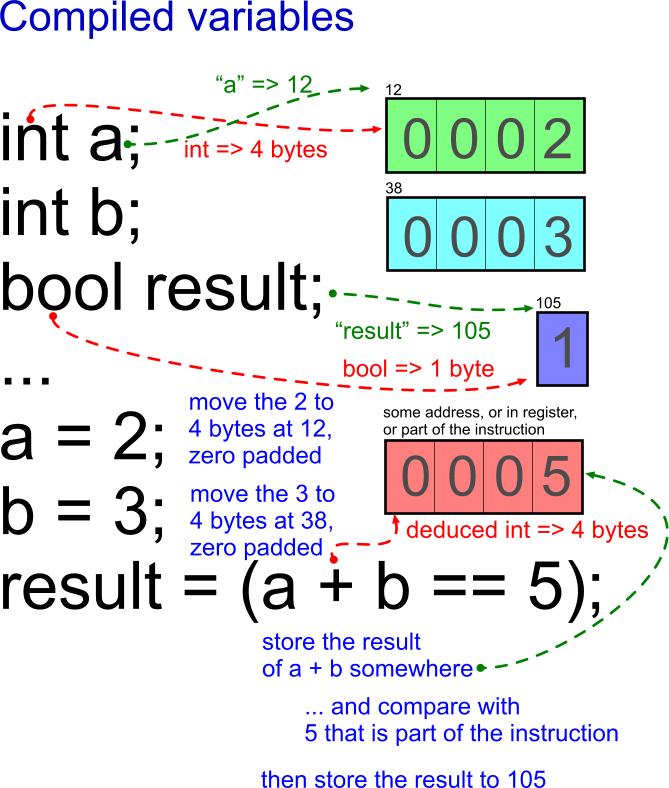

Let's think about the equation a + b = 5 as about the Boolean expression that returns--for the given content of variables a and b--the Boolean value that indicates whether the values are the solution for the equation.

This is a fragment of a source code in the C language. The "C" is not important here. Let it simply be the example of a classical procedural compiled language. In such case, the source text is converted to the machine code via a compiler and a linker. The names of the variables are totally replaced by addresses, by register names/numbers, or the values are optimized to be the parts of the generated machine instructions. There is no trace of strings like "a", "b", or "result" in the generated executable. The only exception is when you generate so called debug version of the executable and you explicitly tell the compiler to remember the original names from the source code; however, the computer does not need that. Only the human, the programmer wants the names be present in the debug info to make the compiled code more readable when debugging.

This is a fragment of a source code in the C language. The "C" is not important here. Let it simply be the example of a classical procedural compiled language. In such case, the source text is converted to the machine code via a compiler and a linker. The names of the variables are totally replaced by addresses, by register names/numbers, or the values are optimized to be the parts of the generated machine instructions. There is no trace of strings like "a", "b", or "result" in the generated executable. The only exception is when you generate so called debug version of the executable and you explicitly tell the compiler to remember the original names from the source code; however, the computer does not need that. Only the human, the programmer wants the names be present in the debug info to make the compiled code more readable when debugging.

From that point of view, a name of a variable to a human programmer is in the similar relation as an address of a memory space to a processor. The name of the variable is directly bound to the address. Or YOU work with the name as with the string (in the source code) or the COMPILER works with the address that is the result of the compilation of the name of the variable (in the binary, executable code).

Technical representation of a variable

Technically, the variable needs the memory space and the identification to be useful for a program. The identification without the memory space makes no sense -- one cannot store anything inside. The memory space without the identification is useless either -- one cannot access the memory space.

We were speaking about variables in the previous part. However, the same holds for objects, i.e. for the memory space that is used to store the data of the object. Better to say, anything in Python is an object that can be identified, including the things that are called variables in some languages. But stay tuned, the details will be explained later. The topic is not that easy as you may think at first. (There are more situations like that. Say, the strings -- the topic "well known from the time of written history". Or not? See http://diveintopython3.org

The memory address serves as a good technical identifier. It is unambiguous. Moreover, you need no transformation to get the information where the memory is located. The major Python implementations also take that approach -- the address is equal to the technical identification of any variable (or of any object). Having any object obj in Python, you can apply the built-in function id(obj) to get the identification. (However, other Python implementations are free to use a different kind of identification in future. Think about a distributed computing environment where there is no single, shared memory address space. The address is ambiguous in such systems unless it is extended by some extra information about the location of the memory/computer.)

What about the size of the reserved memory space? When you need to store a Boolean value, one bit would be enough. As you cannot address one single bit, the smallest possible piece of memory, one byte, is often used. If you want to store an integer, you usually think about 4 or more bytes. It depends on the programming language, on the compiler, and also on the hardware. (In Python, integer variables are not that limited. The space for one integer value may vary depending on the actual value.)

To summarize, the memory space depends on the type of the value and sometimes also on the actual value (think about a string of a different length in whatever language]. In compiled languages, the size of trivial types is known. Therefore, the size of memory is related to the type. However, the information about the type is used/processed only during the compilation. Similarly to variable names, the type is used only to check statically if the things are done in a correct way. During the compilation, the type-name information is lost, and the related size of memory is present as numbers in the executable.

Where the memory space is located?

Think about a simple situation. You have a normal computer with one processor and with one RAM (Random Access Memory). The RAM address goes (for simplicity) from zero to 4.000.000.000. The variable needs say eight bytes. Where the eight bytes are to be located?

"I don't care." And you are right. The machine and the compiler should care. Anyway, the code needs to know the location. Where the knowledge about the location is stored?

The compiled-language sources are processed by the compilers that consume the source texts and convert them to the machine code. In such case, the knowledge about the location must be hidden somewhere in the code. Otherwise the code would not be able to access that portion of memory (i.e. what once was the name of the variable). In the case, the address of the memory must be hidden in the code. But how?

Roughly said (i do not want to go into too much details):

The address can be a constant, and the related memory was once (in the source text) called a static variable. Such a variable keeps the content during the lifetime of the program and its content changes only when it is explicitly changed by the code.

The address is computed relatively -- by adding the numeric offset to some base address (in some register) of the memory subspace. (This is done as the part of the low-level instruction behaviour -- no human-related programming like "take the register content, add 5, and assign...) Think about a function that uses its own, local variables. When the function is called, it gets a block of memory big enough for storing its local variables. The local variable is located relatively to the beginning of the allocated block. The block is released when the function returns.

The memory is allocated dynamically, during the running time via calling some function (like malloc() in C) or via some other action bound to the dedicated keyword (like new). In such case, the address is known only after the data space was created (when the program is already running), and the address must be stored somewhere for the later reference. No name is bound to such memory space -- even in compiled languages. The size was deduced from the prescribed type (new) or it was given explicitly to the function (malloc()). In the first case, the compiler keeps track about the size derived from the type. In the later case (malloc()), a programmer is responsible for working correctly within the allocated space.

Scripting languages

There was a time when so called scripting languages appeared (think about the Unix shell scripts or the Windows batch files). A command processor (say bash or cmd takes the source text called a script line by line and interprets the commands written in the file. These languages are also called interpreted. This is because of when and how the source text is processed when the script is launched. There are no binary native instructions stored in the executed script file. The source text is read and interpreted immediately. Of course, the script has to be interpreted by some binary executable program--the interpreter--that is capable to do the actions prescribed in the script. (This is done via association with the script extension or via special command at the beginning of the script.) Because of the way how it works, the interpreted languages are not so fast, not so powerful in comparison with compiled languages, and also their data types are somehow more limited. Often, the part of a name of a variable indicates also the type.

Simply said, the work with variables is a bit magical in the scripting languages. You never need to know their memory address. As you usually write only simple scripts, you usually do not want to build more complex data structures. You do not care how the memory is allocated. (Anyway, the memory must be allocated dynamically.)

The interpreted languages may often be weakly typed. Simply said, if the string value looks like a number, it can be treated as a number. Because of that, you can use such value with numeric operators, for example.

The simpler languages often play tit for tat. And we sometimes need something in between the simple scripting languages and the extremely powerful (fast running and expressive) compiled languages. This can be done, and Python is the example of such language. Before speaking about details of (also called) dynamic languages, we need to learn something more about indirect access to memory space (i.e. to the stored values). It is a natural feature also in compiled languages; however, it is essential for dynamic languages.

Pointers

Oh the bloody pointers! It is the theme where many programmers with less formal education and/or with not enough greed for knowledge fail. When looking at, say, C++ source code without the knowledge, many students just give up and switch off their brain. Possibly they have never got the satisfactory explanation. Let's enhance our imagination using the following pictures. Let's start the hard way -- from the magical C++ source code to the abstract pictures. (No problem if you do not know the C++ language. I will explain the necessary things.)

Let's start with:

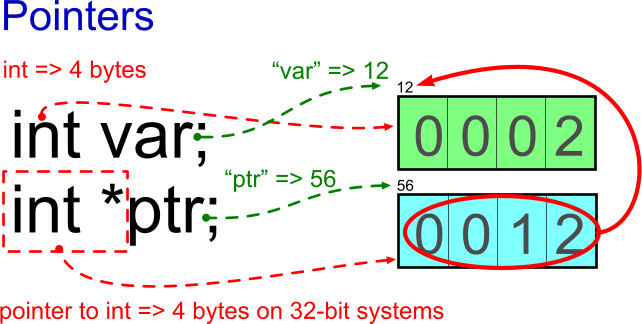

int var;

int *ptr;The first line declares that there will be the variable named var of the type int (means integer). The second line looks almost the same. There will be variable ptr somehow related to the type int. But what means the star? The star changes the meaning of the declaration of the variable. The variable will not be of the int. It will be of the pointer to int type, instead. Have a look at the following picture:

The picture shows that both var and ptr variables need their memory space. In other words, pointer variable is also a variable. A pointer variable also stores a value. The value could be called a pointer value. Basically, it is the address of another memory. As explained earlier, any variable needs memory space and the identification. Any pointer variable needs that much space to be able to store the address. If the hardware is capable to address directly say 4 GB (i.e. 2^32 bytes), then the variable needs 32 bits (4 bytes) of memory to store the address. However, if we use the 64-bit Operating System, then we say we can (theoretically) directly address 2^64 bytes of memory. I do not believe you have that much memory in your computer. Anyway, the pointer variables need 8 bytes in such case.

The picture shows that both var and ptr variables need their memory space. In other words, pointer variable is also a variable. A pointer variable also stores a value. The value could be called a pointer value. Basically, it is the address of another memory. As explained earlier, any variable needs memory space and the identification. Any pointer variable needs that much space to be able to store the address. If the hardware is capable to address directly say 4 GB (i.e. 2^32 bytes), then the variable needs 32 bits (4 bytes) of memory to store the address. However, if we use the 64-bit Operating System, then we say we can (theoretically) directly address 2^64 bytes of memory. I do not believe you have that much memory in your computer. Anyway, the pointer variables need 8 bytes in such case.

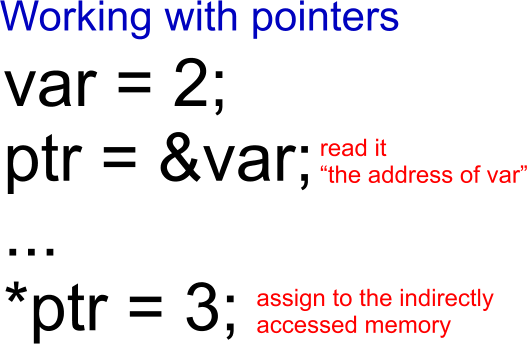

Let's assign the values to the variables to see how to work with pointers:

You should already be very familiar with the fist assignment of the 2 to the var variable. The earlier picture shows that the four bytes at the address 12 are filled with the binary representation of the value 2. Notice, that the variable was given the memory space at the address 12. The notation &var means the address of the variable. Now, the ptr variable is ready to store the address. This way, the address 12 can be assigned to the pointer variable (see the second line on the picture).

You should already be very familiar with the fist assignment of the 2 to the var variable. The earlier picture shows that the four bytes at the address 12 are filled with the binary representation of the value 2. Notice, that the variable was given the memory space at the address 12. The notation &var means the address of the variable. Now, the ptr variable is ready to store the address. This way, the address 12 can be assigned to the pointer variable (see the second line on the picture).

Having the pointer value (i.e. the address 12) inside the pointer variable that is located on address 56 (see the picture above), we can access the memory space of the var variable also indirectly, through the pointer. To do that, we have to read the content of the variable ptr located at the address 56, and then we have to use its content (12) to locate the memory at that address. That's all! No extra magic. Well, the syntax may have look magically...

The *ptr (with the star at in front of the name of the variable says: take the content of the ptr and use it for indirect access to another part of memory. The process is named dereferencing. The pointer variable refers to some other memory, and we want to access it. As we have to explicitly use the star in front of the pointer variable, it is called explicit dereferencing.

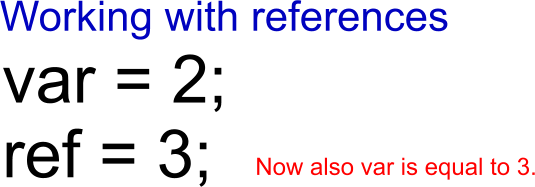

Having the access to the part of memory means also the write access. The last line on the picture shows that the memory space is assigned by new value 3. If you now read the variable var, you would get the value 3. The memory space belongs to the var variable, but from now on it is not the only way how it can be accessed.

Does the pointer theme look so difficult to you now? Is there anything more to be said? Thinking about the principle, then nothing. But, well, yes.

When talking about variables in compiled languages, we have said that the compiler converts the name to the address, deduces the size from the type of the variable, and uses the type for static checking during the compilation. Is there anything about types at the last picture? Well, yes.

The *ptr = 3; assigns the integer value. The integer value can be assigned only to an integer variable. How the compiler knows that this assignment is correct? The answer is not that difficult. It is more difficult to spot that the check must be done by the compiler.

The ptr was declared as pointer to int. This way, it says that it point to the memory of the size that is capable to store the int value. In other words, pointers in compiled languages are usually bound with some type. And again, the type is used only for checking during compilation (hence the name statically typed languages). The information about the type disappears when generating the binary executable. Anyway, the pointers are typed in the compiled languages.

What about untyped pointers? Are they possible? Is it possible to have a pointer to any type? The short answer is yes. The pointer variable itself requires always the same amount of memory (4 bytes on 32-bit OS, 8 bytes on 64-bit OS). It simply stores the address. The problem is that then the compiler does not know how big is the block of memory that is pointed to. The pointer variable stores no knowledge about the size of the target. The programmer have to get the information from somewhere else. One of the possibilities is to store the size of the pointed structure at the beginning of the structure.

What else? NULL. Or the similar name. This is the special value that can be assigned a pointer variable of any type. This means that you can assign it also, say, to the pointer to int. This is the only pointer-value constant available. It says: "the pointer points to nowhere." Naturally, you cannot de-reference such pointer. The "nowhere" can never be accessed. If you try, the screaming sound... kidding, not screaming actually... the error is somehow announced.

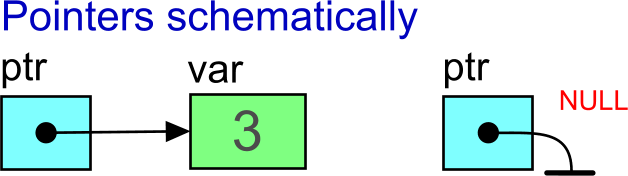

Drawing variables and pointers symbolically

Our brain likes thinking in abstractions. "No boring numbers, please. I tend to forget them." We always solve (sub)problem in our head first, and only then we write the idea down. We use our imagination. If it is too much to keep it in our brain, we draw it on a paper...

Also, we need some graphical abstraction to be able to share what we mean with others. We want to keep the picture as abstract as possible, as simple as possible, but not simpler than needed.

The memory space for the variable is usually drawn as rectangle. Again, a pointer variable is also a variable -- it needs its rectangle too. However, we want the pointer value be more abstract. (Recall what the brain have said about the numbers. Anyway, we do not know the exact addresses and we do not care.) The only important thing for us is that the value points to another memory space (hence the pointer). And the pointer should be pointed, right? ;) To summarize, the pointer value is drawn as a fat dot with an arrow pointed to the other memory-space rectangle.

The memory space for the variable is usually drawn as rectangle. Again, a pointer variable is also a variable -- it needs its rectangle too. However, we want the pointer value be more abstract. (Recall what the brain have said about the numbers. Anyway, we do not know the exact addresses and we do not care.) The only important thing for us is that the value points to another memory space (hence the pointer). And the pointer should be pointed, right? ;) To summarize, the pointer value is drawn as a fat dot with an arrow pointed to the other memory-space rectangle.

We also do not care how the NULL is implemented. The only interesting feature is that it points to nowhere. The "electric ground" mark is usually used. That mark was very usual and well known to those who worked with first computers -- not counting Charles Babbage (http://en.wikipedia.org/wi

Now, repeat "the pointers" until you really know what they are about.

References

The term references often causes confusion. The main reason is that it can be used in different contexts.

The more abstract point of view is based on the idea that the reference value allows you to access some data (memory space) indirectly. From that abstract point of view, the plain old pointers are also references.

However, the terms references and pointers are often discussed together, and there are some differences emphasized between them in the case. Usually, the references are said to be de-referenced automatically when used (unlike the pointers).

The confusion has roots also in the fact that different programming languages think differently about references. Some languages do not use the term references, some languages do not know pointers. Some languages do not have any special syntax for references, and the fact of working with references internally may be completely hidden (this is also the case of Python -- see later).

Back to the old compiled languages, here C++.

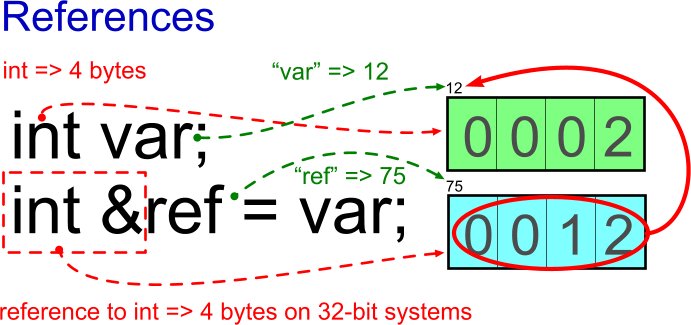

The image shows the C++ syntax. Ignore the syntactic details if you do not know the language. What is important, the ref variable must be initialized when declared. The reason is that it must always contain a reference to some already existing variable, i.e. to its allocated memory space.

The image shows the C++ syntax. Ignore the syntactic details if you do not know the language. What is important, the ref variable must be initialized when declared. The reason is that it must always contain a reference to some already existing variable, i.e. to its allocated memory space.

Here the ref variable was located by the compiler/linker/loader at the address 75 (not important). The important is that its memory space was filled with the address of the var variable immediately. The C++ restriction is that you cannot change the reference variable later. Any usage of the ref has the same effect as using the variable var.

The main difference from pointers is how the references look in the source code. Once the reference variable is set, you can use it as if it was another name for the pointed variable. In the example, the reference variable is named ref which forces you to think this way about it. But imagine if it was named myVar. When using a reference variable, it looks the same as if you worked with a normal, simple variable. It is because the automatic de-reference is done (by compiler, for you). Anyway, the target memory space is still accessed indirectly.

The main difference from pointers is how the references look in the source code. Once the reference variable is set, you can use it as if it was another name for the pointed variable. In the example, the reference variable is named ref which forces you to think this way about it. But imagine if it was named myVar. When using a reference variable, it looks the same as if you worked with a normal, simple variable. It is because the automatic de-reference is done (by compiler, for you). Anyway, the target memory space is still accessed indirectly.

In other words, when you do not see the reference-variable declaration, you are not able to say if you work with a simple variable or (indirectly) with another variable.

References for Python

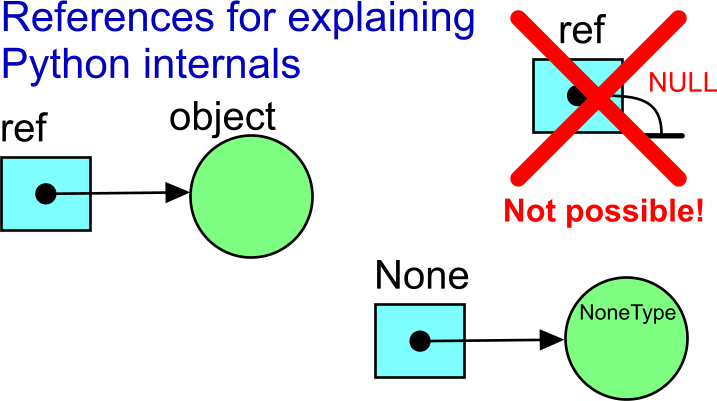

Python uses references internally a lot. Let's define the term reference the way we need for explanation of the Python internals.

We usually do not draw the references on the paper the same way as we do with pointer-based data structures. Anyway, we can draw them the same way when explaining the internals. Actually, the references are used in Python the very same way as pointers are used in other languages. However, it is hidden from the programmer. The reference value in Python (as elsewhere) needs always the same memory space to be stored (4 bytes on 32-bit systems, 8 bytes on 64-bit system).

We usually do not draw the references on the paper the same way as we do with pointer-based data structures. Anyway, we can draw them the same way when explaining the internals. Actually, the references are used in Python the very same way as pointers are used in other languages. However, it is hidden from the programmer. The reference value in Python (as elsewhere) needs always the same memory space to be stored (4 bytes on 32-bit systems, 8 bytes on 64-bit system).

However, Python is a dynamic language where memory space for the objects is always allocated in run-time, and where the name of any variable is kept intentionally in a string form inside Python's internal data structures.

Why to call them references and not pointers? This is because you will find no explicit de-referencing when working with Python. But that's not all! There is one more indirection level when working with variables. The topic will be discussed more in part 3.

A side note: There is nothing like NULL value for Python references. This would break the concept of references. However, there is the single object named None that plays the same role. Whenever another object refers to None, it means that there is nothing more interesting there (if the fact is not interesting on its own).

Topics to be discussed in part 3

- Python as a dynamic language

- everything in Python is an object

- trivial Python built-in types

- container built-in types

- what is behind the assignment operation in Python

- containers and references

- Python approach variables (dict of name->reference)

- where the types are stored in Python

Have a question about something in this article? You can receive help directly from the article author. Sign up for a free trial to get started.

Comments (6)

Author

Commented:ad 1) There is no part 3 yet.

ad 2) They are not abstract ideas in this part. Rather, they are simplified but very concrete ideas than many beginners are not aware of. I needed to explain the idea of a reference first as I consider it essential when explaining how Python works.

ad 3) This is a serie of articles. More Python-related things will be shown in the next part.

ad 4) Even the computers may also not be that neccessary. On the other hand, I believe that understanding the presented details IS neccessary.

You are free to present your own view ;) I have no problem with that.

Commented:

Author

Commented:Commented:

I do not understand the difference between

*

&

& is the address of var

* assign to the indirectly addressed memory

do I need * to change value of the pointer

Author

Commented:View More