Browse All Articles > Access Fast Lookup in Finance

Introduction

I often hear the opinion that "Access isn't fit for serious applications". Finance is of course very serious... and extremely serious in Switzerland; needless to say that I never expect much business from that particular branch. The main reasons are of course security and volume. You don't want numbered account information travelling on a laptop, and you won't handle a million daily transactions or fifty thousand cash distributors with Access. Let's be serious.

But there are also many small financial institutions like fund managers, and clients of finance like pension funds. Their needs in terms of data management often comes down to a few dozen items, each with a couple of thousand numbers in a small selection of currencies, and only a few active users. They still hold the opinion that "Access can't handle it", even while happily attempting to do so with Excel...

When analysing a project in this context, it appears that the main, or only remaining problem is the difficulties in performing lookups. In a spreadsheet architecture, this is solved by dependency chains. Since financial historical data is very much static, the update chain of depending cells is rarely triggered, so the overall performance is good even when numerous complex lookup operations are involved. Not so with a database architecture, where all derived data is recomputed every time a query is run.

This article will show that the nature of financial lookup operations makes them hard to handle in Access, enforcing the prejudice. However, by using "fast table lookup" techniques, this difficulty can be overcome, with great success.

A demo file containing the skeleton of a portfolio management system is provided, with all needed lookup functions, but only a simplified support module.

If you wish to implement similar functions in your application, please read also Access Techniques: Fast Table Lookup Functions, which contains further demo files. The other way around, the present article serves as an elaborate example, illustrating one field of application for them.

Now what's so special about finance, seriously?

Currency Values and Exchange Rates

This section is a crash-course in currencies and rates; it briefly introduces the concepts I needed to understand before I could even start planning data structures and processes, when managing multiple currencies was a requirement.

For most people, and for most programmers, a currency value is just a number. In Access, it's a numeric data type. But that's only one third of the story. When you hear "this watch cost at least one grand", the number 1000 is in fact complemented by two implicit facts: it's an amount in US dollars, and it's today. Thousand Yen (today), or thousand dollars in 1900 would not mean quite the same thing. But for most practical purposes, creating a currency column is all a mere mortal needs to manage money.

In finance, each amount (value, price, cost...) needs three fields: a number, a currency code, and a date. Likewise, in science, each measure needs a number, a unit, and a context (which often includes a date). But unlike science, there are no fixed conversion functions. 20 °C = 68 °F is always true, but 110¥ = 1$ isn't. It has been true two dozen times or more in the last five years (the last time around 2008-08-22) depending on the granularity of the past exchange rates record being examined. We don't know if or when it will ever be true again. At the time of writing, 110 Japanese Yen are worth almost a dollar and a quarter, or one dollar almost 89 Yen.

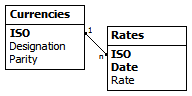

In every multi-currency application, there is a currency exchange calculator, using a table of dated exchange rates. The table structure is similar to this:

![currencies and rates]() Once more a field is missing! A rate needs two currency designations: "from" and "to", e.g. $»¥, ¥»£, £»$. But let's switch to ISO three-letter currency codes. The rate USD/EUR: 1.48825 could mean "one Euro costs 1.49 Dollars", or the inverse figure, 0.67193, "one Dollar sells for 0.67 Euro". But the rate EUR/USD can be a little higher, because selling and buying prices are never exactly the same. Foreign Exchange traders and banks need to make that distinction, but neither is likely to store the minute-by-minute rates from their data streams in an Access database.

Once more a field is missing! A rate needs two currency designations: "from" and "to", e.g. $»¥, ¥»£, £»$. But let's switch to ISO three-letter currency codes. The rate USD/EUR: 1.48825 could mean "one Euro costs 1.49 Dollars", or the inverse figure, 0.67193, "one Dollar sells for 0.67 Euro". But the rate EUR/USD can be a little higher, because selling and buying prices are never exactly the same. Foreign Exchange traders and banks need to make that distinction, but neither is likely to store the minute-by-minute rates from their data streams in an Access database.

In most financial situations, rates are "value rates", averaging buying and selling quotes. So the equation 1 / 1.48825 = 0.67193 is valid to obtain the EUR/USD rate from USD/EUR; and GBP/JPY can be calculated from USD/GBP and JPY/USD -- there is no cost involved in the intermediate transaction. Furthermore, all applications have one home currency, and only rates against that currency are stored. The base currency is the missing field from the data structure: it is a global setting of the application.

That leaves one problem. If the table shows the rates "GBP 1.6482" and "JPY 88.976" for today, USD being the application's base currency, they do not mean the same thing. The first is a "direct" quotation, the value of one pound in home currency, noted USD/GBP, while the second is "indirect", quoting the value in foreign currency of one dollar, noted JPY/USD.

Indirect rates for USD are also called "dollar parity rates", and some applications will use only that kind. They make the columns very readable: every currency/value pair is a way to express the value 'one dollar' today:

1$ = CNY 6.8277 = EUR .67193 = GBP .60672 = JPY 88.976 = RUB 29.000

However, I used to think of Pounds as being ~2¼ Francs (~1¾ more recently), and dollars as being more than one Franc. These are the direct quotations. The multi-currency applications in which I was involved all had at least one or two currencies for which direct quotations were preferable, even internally.

The field 'Parity' is hence a yes/no field describing the directionality of the rate, it could have been called 'Indirect'. This is all rather confusing at first, and the figure below should help. If you want more details, please consult the relevant page on Wikipedia.

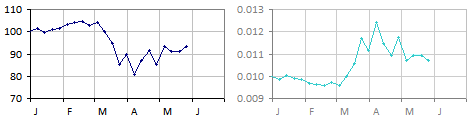

![Zindirian Peso -- six months]() The figure shows six month of weekly exchange rates for the Zindirian Peso (ZIP) against our home currency, the Gemini Mark (GEM), which was severely depreciating in March, followed by some instability. The left chart shows indirect rates starting at 100 ZIP for one GEM; the derived direct chart on the right is flipped vertically * starting at 0.01 GEM for one ZIP, with ZIP appreciating in March... Mathematically equivalent, but semantically opposite!

The figure shows six month of weekly exchange rates for the Zindirian Peso (ZIP) against our home currency, the Gemini Mark (GEM), which was severely depreciating in March, followed by some instability. The left chart shows indirect rates starting at 100 ZIP for one GEM; the derived direct chart on the right is flipped vertically * starting at 0.01 GEM for one ZIP, with ZIP appreciating in March... Mathematically equivalent, but semantically opposite!

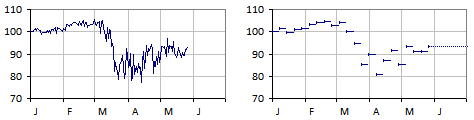

![chart interpretations]() The figure at the left is closer to what really happened: it includes at least daily rates. The figure at the right shows how weekly rates are being used. The missing rates are not interpolated; the value lines are always horizontal. Friday's rate is used until next Thursday. The same principle applies to coarser and finer granularities (monthly budget rates, daily reference rates). A rate is valid until replaced.

The figure at the left is closer to what really happened: it includes at least daily rates. The figure at the right shows how weekly rates are being used. The missing rates are not interpolated; the value lines are always horizontal. Friday's rate is used until next Thursday. The same principle applies to coarser and finer granularities (monthly budget rates, daily reference rates). A rate is valid until replaced.

And that principle is the fundamental mechanism we need to implement in all financial databases.

ZIP-GEM.csv

Basic Financial Lookup

In a 'Transactions' table, we have a record for 2500 ZIP on the 4th of April. What is the value in GEM with weekly rates? There is no matching record -- this is visible in the figure at the right, but there is one for the last day of March, rate 89.7. (On a very detailed chart, we could find that 77.8934 is the accurate rate for that day, or even that hour... but we only have weekly rates.) So we use 89.7, and since the rate is an indirect rate, we divide:

2500 ZIP / 89.7 = 27.87 GEM [31-MAR to 06-APR]

The following week, the rate drops to 80.6, so the same amount would jump to 31.02 GEM.

Getting the rate is a typical case of searching for the "last of something". One way to do it is:

"Give me the first rate you find for the currency before or at the relevant date, in reverse chronological order."

In the case of currencies, there is the added problem of the way the rates are stored. The above assumed an indirect rate, let's try to force a direct rate. Luckily the field Parity can be included through a simple join:

This is our first tool: a lightning fast currency exchange mechanism. Why is it so fast? Let's break it down.

What about an amount that is already in the application's base currency? It doesn't need to be converted. This is easily solved by a test (or perhaps by inserting one single rate of 1.0 for the base currency on 1900-01-01).

A Multi-Currency Application

The same type of lookup will appear in all other time-based track records. Let's follow a fictional development project.

A low-cost simple Portfolio Management system is required by one of our clients; he is thinking perhaps an Excel workbook with "some automation". He doesn't believe that Access can handle it (he is a serious financier), but accepts to look at a proof of concept. So we start building.

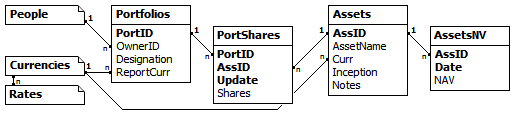

![database structure]() This looks familiar, especially the date fields being part of multi-field keys... The relationship between Assets and their Net Values (NAV) is very much like that between Currencies and Rates. The same is true for Portfolios and Shares or Assets and Shares. We already have the tool for that.

This looks familiar, especially the date fields being part of multi-field keys... The relationship between Assets and their Net Values (NAV) is very much like that between Currencies and Rates. The same is true for Portfolios and Shares or Assets and Shares. We already have the tool for that.

First report: a Portfolio status at any given date. For each asset, find the last prior update in number of shares (check!), the corresponding Net Asset Value (check!) the best exchange rates of both the Asset's base currency and the Portfolio's preferred reporting currency (check!), and calculate the total value (easy!). The query works, so does the report.

Just before the presentation, someone suggests to add the MTD and YTD values (month-to-date and year-to-date return in the report's currency). That takes a little session of head scratching and copy-pasting sub-queries, but it is relatively easy, and still fast. If you enjoy reading SQL, this is the full query.

portfolio-status-query.txt

The Problem

Maybe the demonstration was a success. But now that the real development starts, it becomes apparent that it will be very unpleasant. The problem begins with the last query. It works, and it's even still readable, but let's look at it from an analytical point of view (no need to zoom in).

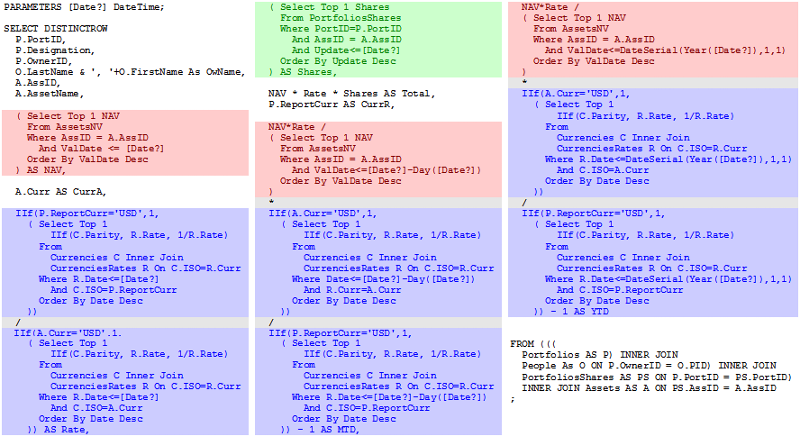

![long query -- colour coded]() The colour coding reveals one lookup for the number of shares in green, three NAV lookups in red (present, last month, and last year), and six rate lookups in blue. What's wrong with that?

The colour coding reveals one lookup for the number of shares in green, three NAV lookups in red (present, last month, and last year), and six rate lookups in blue. What's wrong with that?

Then there is the interaction of complex queries with groups on reports, the difficulty in using complex queries as source for synthetic queries, performing econometric evaluations, etc.

All things considered, the query should look more like this:

So, that's what we need: functions.

The Solution

If you presented the problem to the serious developers next door, he would probably say that this would be trivial in BlingSQL, which supports functions and much more, but since JetSQL doesn't, there isn't a solution.

Although it's technically true, Jet doesn't provide functions, it has very strong ties with Visual Basic, which provides function support "and much more". As a language, it is just as fast and structured as BlingSQL's integrated functions. The serious argument that integrated function will automatically be optimised better doesn't hold in our case, because the DAO library exposes the indexes of the table, for seeking and navigation. A feature not found in Bling, paradoxically.

Note: The long version of what follows is the topic of the article mentioned in the introduction.

In a nutshell, an Access table can be opened as a recordset using a special "table mode". Such a recordset can be assigned any existing index of the table, which is then used in several methods: Seek, MoveFirst/Last, MoveNext/Previous; and properties: NotFound, EOF, BOF. In a financial context, Seek and NoMatch is all we need.

If the table is local, the TableDef's OpenRecordset method creates such a "table mode" recordset. If the primary key is called "PrimaryKey" (the default name), the following lines will display the designation of the "GEM" currency:

With this out of the way, here are a few of the functions in the demo database.

You can test this function in the "currency calculator" provided in the demo.

More functions, including those mentioned earlier, are defined in the demo file, for example:

CurrNAV(Asset, ISO [, Day]) -- NAV converted to ISO

AssetShares(PortID, AssID, Day) -- number of shares (last update)

Inception(Asset) -- inception date of the asset

LastUpdate(PortID, AssID) -- date of last update (or Null)

All of them could be written as a sub-query (or a group of sub-queries).

Before I conclude, here is also an example of a query used to retrieve monthly returns from across the tables, regardless of the update schedule of Assets and related Currencies.

The Demo Application

This tiny application, in Access 2000 format is exactly the "proof of concept" Portfolio application discussed earlier. With one major difference: it doesn't use a single sub-query, but only fast table lookup functions.

To avoid any off-topic navigation issues, it is locked in the year 2000, and uses simplistic interface techniques, including parametric prompting queries. When asked for a date, choose one in the year 2000, and for best results the last day of a month.

One econometric report and two charts show that derived data (obtained from the functions) can be used in higher level constructs. Make sure to change the parity flag of currencies and observe the effect.

The purpose of the demo is really to demonstrate fast table lookup functions in a plausible context, and how they can be used much like integrated functions of other SQL implementations. The interface is only a bonus.

Conclusion

The demo database emerged almost spontaneously while working on the main article about Fast Table Lookup Functions. The first section is part of what I had to learn while working for financial institutions and provided a perhaps superfluous but not unpleasant introduction to the main topic.

The article is also based on real experience. I have used fast lookup functions extensively in three major projects and several smaller ones. The first time, it was in a financial context, a field in which I knew next to nothing. I took pleasure in discovering some econometrics and in the challenge posed by the problem described here.

My gain as developer was the removal of a serious flaw in my perception of Jet. Before that experience, Jet was the "engine". Something I used from the interface or from Visual Basic, but not in any interactive way. Of course I knew I could call VB functions from a query, but these were always interface related. The notion that a function could be used for the benefit of the Engine, to simplify queries or to circumvent limitations, had never occurred to me.

I hope this will inspire fellow Access developers and perhaps, in some small way, change the prejudice against this platform in financial circles.

Markus G Fischer

(°v°)

about unrestricted access

I often hear the opinion that "Access isn't fit for serious applications". Finance is of course very serious... and extremely serious in Switzerland; needless to say that I never expect much business from that particular branch. The main reasons are of course security and volume. You don't want numbered account information travelling on a laptop, and you won't handle a million daily transactions or fifty thousand cash distributors with Access. Let's be serious.

But there are also many small financial institutions like fund managers, and clients of finance like pension funds. Their needs in terms of data management often comes down to a few dozen items, each with a couple of thousand numbers in a small selection of currencies, and only a few active users. They still hold the opinion that "Access can't handle it", even while happily attempting to do so with Excel...

When analysing a project in this context, it appears that the main, or only remaining problem is the difficulties in performing lookups. In a spreadsheet architecture, this is solved by dependency chains. Since financial historical data is very much static, the update chain of depending cells is rarely triggered, so the overall performance is good even when numerous complex lookup operations are involved. Not so with a database architecture, where all derived data is recomputed every time a query is run.

This article will show that the nature of financial lookup operations makes them hard to handle in Access, enforcing the prejudice. However, by using "fast table lookup" techniques, this difficulty can be overcome, with great success.

A demo file containing the skeleton of a portfolio management system is provided, with all needed lookup functions, but only a simplified support module.

If you wish to implement similar functions in your application, please read also Access Techniques: Fast Table Lookup Functions, which contains further demo files. The other way around, the present article serves as an elaborate example, illustrating one field of application for them.

Now what's so special about finance, seriously?

Currency Values and Exchange Rates

This section is a crash-course in currencies and rates; it briefly introduces the concepts I needed to understand before I could even start planning data structures and processes, when managing multiple currencies was a requirement.

For most people, and for most programmers, a currency value is just a number. In Access, it's a numeric data type. But that's only one third of the story. When you hear "this watch cost at least one grand", the number 1000 is in fact complemented by two implicit facts: it's an amount in US dollars, and it's today. Thousand Yen (today), or thousand dollars in 1900 would not mean quite the same thing. But for most practical purposes, creating a currency column is all a mere mortal needs to manage money.

In finance, each amount (value, price, cost...) needs three fields: a number, a currency code, and a date. Likewise, in science, each measure needs a number, a unit, and a context (which often includes a date). But unlike science, there are no fixed conversion functions. 20 °C = 68 °F is always true, but 110¥ = 1$ isn't. It has been true two dozen times or more in the last five years (the last time around 2008-08-22) depending on the granularity of the past exchange rates record being examined. We don't know if or when it will ever be true again. At the time of writing, 110 Japanese Yen are worth almost a dollar and a quarter, or one dollar almost 89 Yen.

In every multi-currency application, there is a currency exchange calculator, using a table of dated exchange rates. The table structure is similar to this:

Once more a field is missing! A rate needs two currency designations: "from" and "to", e.g. $»¥, ¥»£, £»$. But let's switch to ISO three-letter currency codes. The rate USD/EUR: 1.48825 could mean "one Euro costs 1.49 Dollars", or the inverse figure, 0.67193, "one Dollar sells for 0.67 Euro". But the rate EUR/USD can be a little higher, because selling and buying prices are never exactly the same. Foreign Exchange traders and banks need to make that distinction, but neither is likely to store the minute-by-minute rates from their data streams in an Access database.

Once more a field is missing! A rate needs two currency designations: "from" and "to", e.g. $»¥, ¥»£, £»$. But let's switch to ISO three-letter currency codes. The rate USD/EUR: 1.48825 could mean "one Euro costs 1.49 Dollars", or the inverse figure, 0.67193, "one Dollar sells for 0.67 Euro". But the rate EUR/USD can be a little higher, because selling and buying prices are never exactly the same. Foreign Exchange traders and banks need to make that distinction, but neither is likely to store the minute-by-minute rates from their data streams in an Access database.

In most financial situations, rates are "value rates", averaging buying and selling quotes. So the equation 1 / 1.48825 = 0.67193 is valid to obtain the EUR/USD rate from USD/EUR; and GBP/JPY can be calculated from USD/GBP and JPY/USD -- there is no cost involved in the intermediate transaction. Furthermore, all applications have one home currency, and only rates against that currency are stored. The base currency is the missing field from the data structure: it is a global setting of the application.

That leaves one problem. If the table shows the rates "GBP 1.6482" and "JPY 88.976" for today, USD being the application's base currency, they do not mean the same thing. The first is a "direct" quotation, the value of one pound in home currency, noted USD/GBP, while the second is "indirect", quoting the value in foreign currency of one dollar, noted JPY/USD.

Indirect rates for USD are also called "dollar parity rates", and some applications will use only that kind. They make the columns very readable: every currency/value pair is a way to express the value 'one dollar' today:

1$ = CNY 6.8277 = EUR .67193 = GBP .60672 = JPY 88.976 = RUB 29.000

However, I used to think of Pounds as being ~2¼ Francs (~1¾ more recently), and dollars as being more than one Franc. These are the direct quotations. The multi-currency applications in which I was involved all had at least one or two currencies for which direct quotations were preferable, even internally.

The field 'Parity' is hence a yes/no field describing the directionality of the rate, it could have been called 'Indirect'. This is all rather confusing at first, and the figure below should help. If you want more details, please consult the relevant page on Wikipedia.

The figure shows six month of weekly exchange rates for the Zindirian Peso (ZIP) against our home currency, the Gemini Mark (GEM), which was severely depreciating in March, followed by some instability. The left chart shows indirect rates starting at 100 ZIP for one GEM; the derived direct chart on the right is flipped vertically * starting at 0.01 GEM for one ZIP, with ZIP appreciating in March... Mathematically equivalent, but semantically opposite!

The figure shows six month of weekly exchange rates for the Zindirian Peso (ZIP) against our home currency, the Gemini Mark (GEM), which was severely depreciating in March, followed by some instability. The left chart shows indirect rates starting at 100 ZIP for one GEM; the derived direct chart on the right is flipped vertically * starting at 0.01 GEM for one ZIP, with ZIP appreciating in March... Mathematically equivalent, but semantically opposite!

* If you have sharp eyes, you noticed there is a distortion. This is due to the linear scale; there wouldn't be any distortion using logarithmic scales for rates.One other mysterious aspect of the chart is the meaning of the lines joining the Friday rates. Lines suggest a continuous process, the rate dropping or rising smoothly during the week. In reality, the rate fluctuates every day, every hour, every minute... If you zoom in close enough, you will only see individual transactions, at a given time, for a given price; a discontinuous process.

The figure at the left is closer to what really happened: it includes at least daily rates. The figure at the right shows how weekly rates are being used. The missing rates are not interpolated; the value lines are always horizontal. Friday's rate is used until next Thursday. The same principle applies to coarser and finer granularities (monthly budget rates, daily reference rates). A rate is valid until replaced.

The figure at the left is closer to what really happened: it includes at least daily rates. The figure at the right shows how weekly rates are being used. The missing rates are not interpolated; the value lines are always horizontal. Friday's rate is used until next Thursday. The same principle applies to coarser and finer granularities (monthly budget rates, daily reference rates). A rate is valid until replaced.

And that principle is the fundamental mechanism we need to implement in all financial databases.

ZIP-GEM.csv

Basic Financial Lookup

In a 'Transactions' table, we have a record for 2500 ZIP on the 4th of April. What is the value in GEM with weekly rates? There is no matching record -- this is visible in the figure at the right, but there is one for the last day of March, rate 89.7. (On a very detailed chart, we could find that 77.8934 is the accurate rate for that day, or even that hour... but we only have weekly rates.) So we use 89.7, and since the rate is an indirect rate, we divide:

2500 ZIP / 89.7 = 27.87 GEM [31-MAR to 06-APR]

The following week, the rate drops to 80.6, so the same amount would jump to 31.02 GEM.

Getting the rate is a typical case of searching for the "last of something". One way to do it is:

SELECT

T.Amount,

T.Curr,

T.Date,

( Select Top 1 R.Rate

From Rates R

Where R.ISO = T.Curr

And R.Date <= T.Date

Order By R.Date Desc

) As Rate,

T.Amount / Rate As BaseAmount

FROM Transactions;"Give me the first rate you find for the currency before or at the relevant date, in reverse chronological order."

In the case of currencies, there is the added problem of the way the rates are stored. The above assumed an indirect rate, let's try to force a direct rate. Luckily the field Parity can be included through a simple join:

SELECT

T.Amount,

T.Curr,

T.Date,

( Select Top 1

IIf(Parity, 1/R.Rate, R.Rate)

From

Currencies C Inner Join

Rates R On C.ISO = R.ISO

Where C.ISO = T.Curr

And R.Date <= T.Date

Order By R.Date Desc

) As Rate,

T.Amount * Rate As BaseAmount

FROM Transactions;This is our first tool: a lightning fast currency exchange mechanism. Why is it so fast? Let's break it down.

C.ISO = T.Curr -- Jet will recognise a key table join

C.ISO = R.ISO -- an explicit key table join

R.Date <= T.Date -- criteria on the second key field

Order By R.Date Desc -- reverse key sort order

Select Top 1 -- but there is no need to sort

There might even be room for minute improvements, but again, this is not the place.

What about an amount that is already in the application's base currency? It doesn't need to be converted. This is easily solved by a test (or perhaps by inserting one single rate of 1.0 for the base currency on 1900-01-01).

A Multi-Currency Application

The same type of lookup will appear in all other time-based track records. Let's follow a fictional development project.

A low-cost simple Portfolio Management system is required by one of our clients; he is thinking perhaps an Excel workbook with "some automation". He doesn't believe that Access can handle it (he is a serious financier), but accepts to look at a proof of concept. So we start building.

This looks familiar, especially the date fields being part of multi-field keys... The relationship between Assets and their Net Values (NAV) is very much like that between Currencies and Rates. The same is true for Portfolios and Shares or Assets and Shares. We already have the tool for that.

This looks familiar, especially the date fields being part of multi-field keys... The relationship between Assets and their Net Values (NAV) is very much like that between Currencies and Rates. The same is true for Portfolios and Shares or Assets and Shares. We already have the tool for that.

( Select Top 1 N.NAV

From AssetsNV N

Where N.AssID = [Asset ID?]

And N.Date <= [Report Date?]

Order By N.Date Desc

) As NAV,

( Select Top 1 S.Shares

From PortShares S

Where S.PortID = [Portfolio ID?]

And S.AssID = [Asset ID?]

And S.Update <= [Report Date?]

Order By S.Update Desc

) As Shares,First report: a Portfolio status at any given date. For each asset, find the last prior update in number of shares (check!), the corresponding Net Asset Value (check!) the best exchange rates of both the Asset's base currency and the Portfolio's preferred reporting currency (check!), and calculate the total value (easy!). The query works, so does the report.

Just before the presentation, someone suggests to add the MTD and YTD values (month-to-date and year-to-date return in the report's currency). That takes a little session of head scratching and copy-pasting sub-queries, but it is relatively easy, and still fast. If you enjoy reading SQL, this is the full query.

portfolio-status-query.txt

The Problem

Maybe the demonstration was a success. But now that the real development starts, it becomes apparent that it will be very unpleasant. The problem begins with the last query. It works, and it's even still readable, but let's look at it from an analytical point of view (no need to zoom in).

The colour coding reveals one lookup for the number of shares in green, three NAV lookups in red (present, last month, and last year), and six rate lookups in blue. What's wrong with that?

The colour coding reveals one lookup for the number of shares in green, three NAV lookups in red (present, last month, and last year), and six rate lookups in blue. What's wrong with that?

It has twenty tables. Still below the 32-table limit, but not by much. Anything more complex than a simple status report might hit the limit or become too difficult to evaluate or optimise for Jet.

It isn't modular. It was easy to build, thanks to copy-paste, but I don't want to edit, debug, or maintain it. We no longer have an exchange rate engine, but an army of them.

It isn't portable. Each sub-query has subtle differences with all others, highly specific to the context. Copy-paste is good, but the right details must be adjusted every time.

It isn't documented, and cannot be documented internally.

If this is a simple routine query, will all queries be like that?

What if the database becomes just slightly more complex? If the Assets are in fact Funds, distributing dividends, performing splits and joins, re-basing their base NAV yearly? Suddenly there will be four or five tracks for each Asset, which need to be combined to compute a value. If the Portfolio needs a multi-currency cash side-account, it can create a whole new group of exchange rate sub-queries.

Then there is the interaction of complex queries with groups on reports, the difficulty in using complex queries as source for synthetic queries, performing econometric evaluations, etc.

All things considered, the query should look more like this:

PARAMETERS [Date?] DateTime;

SELECT DISTINCTROW O.*, P.*, A.*,

CurrNAV(A.AssID,P.ReportCurr,[Date?])+0 AS NAV,

NAV/CurrNAV(A.AssID,P.ReportCurr,[Date?]-Day([Date?])+1)-1 AS MTD,

NAV/CurrNAV(A.AssID,P.ReportCurr,DateSerial(Year([Date?]),1,1))-1 AS YTD,

AssetShares(P.PortID,A.AssID,[Date?])+0 AS Shares,

Shares*NAV AS Total

FROM ((

Portfolios AS P INNER JOIN

People As O On P.OwnerID = O.PID) INNER JOIN

PortfoliosShares AS S ON P.PortID = S.PortID) INNER JOIN

Assets AS A ON S.AssID = A.AssID

WHERE S.Update<=[Date?];So, that's what we need: functions.

The Solution

If you presented the problem to the serious developers next door, he would probably say that this would be trivial in BlingSQL, which supports functions and much more, but since JetSQL doesn't, there isn't a solution.

Although it's technically true, Jet doesn't provide functions, it has very strong ties with Visual Basic, which provides function support "and much more". As a language, it is just as fast and structured as BlingSQL's integrated functions. The serious argument that integrated function will automatically be optimised better doesn't hold in our case, because the DAO library exposes the indexes of the table, for seeking and navigation. A feature not found in Bling, paradoxically.

Note: The long version of what follows is the topic of the article mentioned in the introduction.

In a nutshell, an Access table can be opened as a recordset using a special "table mode". Such a recordset can be assigned any existing index of the table, which is then used in several methods: Seek, MoveFirst/Last, MoveNext/Previous; and properties: NotFound, EOF, BOF. In a financial context, Seek and NoMatch is all we need.

If the table is local, the TableDef's OpenRecordset method creates such a "table mode" recordset. If the primary key is called "PrimaryKey" (the default name), the following lines will display the designation of the "GEM" currency:

With CurrentDb("Currencies").OpenRecordset

.Index = "PrimaryKey"

.Seek "=", "GEM"

If .NoMatch Then

MsgBox "No GEM was found."

Else

MsgBox "A GEM is a " & !Designation

End If

End WithWith this out of the way, here are a few of the functions in the demo database.

Function IsParity(ISO) As Boolean

With GetTable("Currencies")

.Seek "=", ISO

If Not .NoMatch Then IsParity = !Parity

End With

End FunctionFunction RateBC(ByVal ISO As String, ByVal Day As Long)

If ISO = BASE_CURR Then RateBC = 1: Exit Function

RateBC = Null

With GetTable("CurrenciesRates")

.Seek "<=", ISO, Day

If .NoMatch Then Exit Function

If !Curr <> ISO Then Exit Function

If IsParity(ISO) Then

RateBC = !Rate

Else

RateBC = 1 / !Rate

End If

End With

End FunctionFunction XChange(Amount, FromC, ToC, Optional ByVal Day)

If FromC = ToC Then XChange = Amount: Exit Function

If IsNull(Day) Then XChange = Null: Exit Function

If IsMissing(Day) Then Day = Date

XChange = Amount / RateBC(FromC, Day) * RateBC(ToC, Day)

End FunctionYou can test this function in the "currency calculator" provided in the demo.

More functions, including those mentioned earlier, are defined in the demo file, for example:

CurrNAV(Asset, ISO [, Day]) -- NAV converted to ISO

AssetShares(PortID, AssID, Day) -- number of shares (last update)

Inception(Asset) -- inception date of the asset

LastUpdate(PortID, AssID) -- date of last update (or Null)

All of them could be written as a sub-query (or a group of sub-queries).

Before I conclude, here is also an example of a query used to retrieve monthly returns from across the tables, regardless of the update schedule of Assets and related Currencies.

PARAMETERS [Enter Currency: (USD)] Text(3);

SELECT

A.AssID,

DateSerial(2000,Z.M+1,0) AS EOM,

( CurrNAV(A.AssID,Nz([Enter Currency: (USD)],'usd'),EOM)

/ CurrNAV(A.AssID,Nz([Enter Currency: (USD)],'usd'),DateSerial(2000,Z.M,0))

- 1

) AS Return

FROM Assets A, zsMonths Z

ORDER BY A.AssID, Z.M;The Demo Application

This tiny application, in Access 2000 format is exactly the "proof of concept" Portfolio application discussed earlier. With one major difference: it doesn't use a single sub-query, but only fast table lookup functions.

To avoid any off-topic navigation issues, it is locked in the year 2000, and uses simplistic interface techniques, including parametric prompting queries. When asked for a date, choose one in the year 2000, and for best results the last day of a month.

One econometric report and two charts show that derived data (obtained from the functions) can be used in higher level constructs. Make sure to change the parity flag of currencies and observe the effect.

The purpose of the demo is really to demonstrate fast table lookup functions in a plausible context, and how they can be used much like integrated functions of other SQL implementations. The interface is only a bonus.

The interface is minimalistic in style and scope. Feel free to dissect it and recycle any parts, but please ask any question you might have about it in the general forums, and not in the article comments.FastLookupFinance.mdb

Conclusion

The demo database emerged almost spontaneously while working on the main article about Fast Table Lookup Functions. The first section is part of what I had to learn while working for financial institutions and provided a perhaps superfluous but not unpleasant introduction to the main topic.

The article is also based on real experience. I have used fast lookup functions extensively in three major projects and several smaller ones. The first time, it was in a financial context, a field in which I knew next to nothing. I took pleasure in discovering some econometrics and in the challenge posed by the problem described here.

My gain as developer was the removal of a serious flaw in my perception of Jet. Before that experience, Jet was the "engine". Something I used from the interface or from Visual Basic, but not in any interactive way. Of course I knew I could call VB functions from a query, but these were always interface related. The notion that a function could be used for the benefit of the Engine, to simplify queries or to circumvent limitations, had never occurred to me.

I hope this will inspire fellow Access developers and perhaps, in some small way, change the prejudice against this platform in financial circles.

Markus G Fischer

(°v°)

about unrestricted access

Have a question about something in this article? You can receive help directly from the article author. Sign up for a free trial to get started.

Comments (1)

Author

Commented:The acting editor was again aikimark, who did an excellent job in reviewing the content and the language. More than language, in fact, because he pointed to some flaws in graphical semiology as well, when the charts and illustrations could be misunderstood. If you do understand the article at all, please join your thanks to mine for his time and his pertinence.

If the article also helped, please click 'yes' above. If it helped only a little, click only a little!

(°v°)