Browse All Articles > Python illustrated (part 3)

"The time has come," the Walrus said,This part describes how variables and references (see parts 1 and 2) fit with Python, and how the clearly strange behaviour is not that strange when you know only a little bit more about the Python internals. Some people may say: "Hey, they are not Python basics at all!" The reality is that not having that little tiny bit of Python knowledge you will once stand schocked, with open mouth, staring at the behaviour of your program. Especially when you ARE a programmer (used to a compiled language).

"To talk of many things:

Of sets--and lists--and dictionaries--

Of variable kinks--

And why you see it changing not--

And why so strange are strings."

If you find anything less understandable about variables and references in this article, have a look at Python illustrated (part 2). Also, your feedback is warmly welcome. It will form the problems illustrated in part 4.

Summary for Python variables/objects

You may not like to read a lot of "theory" first, and you may want to search where the conclusion is. "Does it make sense for me to read further?" Good news for you -- the summary from Python point of view comes first:

1. Everything in Python is an object. Any object has its unique technical identification (the memory address). The information about its type is kept inside the object.

2. The simplest objects are few constants, numeric values, and strings. They are also stored as objects which means they have their own identification. Once they are created, they cannot change their content. They are immutable.

3. More-complex built-in objects are lists, tuples, dictionaries, and sets. They contain only references to other objects, not the objects itself. Let's call them containers (as it is usual also in other languages). The references are untyped. The type is bound to the target object.

4. Any "native" assignment in Python means assigning the reference value. It refers the target object that represents the assigned value. In other words, there will be one more counted reference to the target object after the assignment (counted by the target object).

5. If any object is named, the name is stored as a key in one of the internal Python dictionary structures. The reference to the value object is the value of the dictionary item.

Now slowly, with pictures.

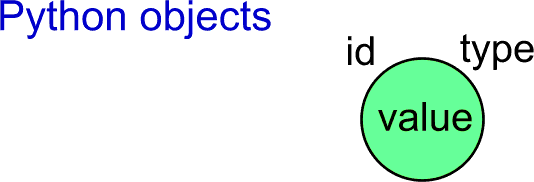

Everything in Python is an object

Objects are not the new thing these days any more. Objects as instances of their classes can be found everywhere. Is there anything special about them in Python?

Every object in Python has its unique identification, and it is of some type (i.e. instance of some class). The object can exist without any name. The only two requirements for its existence are: 1) it must be created, and 2) it must be accessible via at least one reference. (Nothing very special.)

Simplest Python objects

The very basic objects in Python are boolean values (True, False), numeric values (int, float, complex), strings (plus some more).

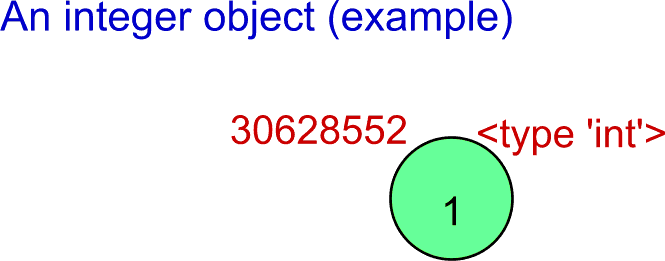

The most natural simple things in any programming language are integer values and integer variables. It is so natural that you can hardly imagine how the integer value could be expressed better than by simply typing the textual representation of the number in the source file. What does it mean when we put it together with "everything in Python is an object"?

Run the Python interpreter in the interactive mode (simply type python without arguments in you console window) and try the following:

c:\tmp\___python\__articles\03pythonVariables>python

Python 2.7.1 (r271:86832, Nov 27 2010, 17:19:03) [MSC v.1500 64 bit (AMD64)] on win32

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> id(1)

30628552L

>>> a = 1

>>> id(a)

30628552L

>>> b = 3 - 2

>>> b

1

>>> id(b)

30628552L

>>> id(5 - 4)

30628552L Notice that simply typing 1 in the source code leads to the creation of the object that represents the value. Looking better at the lines above, the id() function returns always the same identification independently on how you have got the value. Then it must mean that all the cases share the same object of the integer type with the value 1. This is a kind of optimization that does not affect the solved problem. Actually, only some small integers have "a fixed identification". If you try it with bigger integer values, separate objects are created. Try (or read and believe) the following:

Notice that simply typing 1 in the source code leads to the creation of the object that represents the value. Looking better at the lines above, the id() function returns always the same identification independently on how you have got the value. Then it must mean that all the cases share the same object of the integer type with the value 1. This is a kind of optimization that does not affect the solved problem. Actually, only some small integers have "a fixed identification". If you try it with bigger integer values, separate objects are created. Try (or read and believe) the following:

>>> a = 1

>>> b = 1

>>> id(a)

30628552L

>>> id(b)

30628552LHere the identifications are the same. But try it with bigger numbers:

>>> a = 1500000

>>> b = 1500000

>>> id(a)

36576600L

>>> id(b)

36576576LThe identifications now differ. The internal optimization was not used for the case.

If you are interested in more details, have a look for example at Laurent Luce's Blog, "Python integer objects implementation", http://www.laurentluce.com

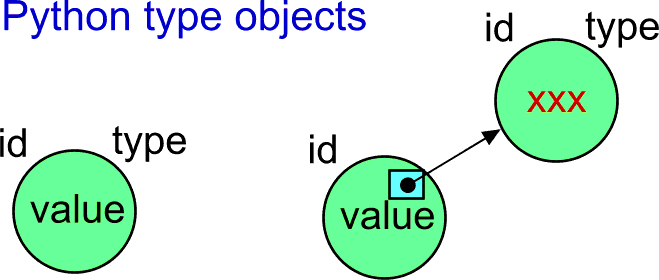

A note about the type

Actually, the instance of the object (its memory footprint) should be as small as possible. This means that the object itself should not store all details common for all instances of the same class. In other words, it should NOT store also details about its type. Technically, it is better to share a reference to another block of information -- also expressed as an object in Python, like this...

There is another built-in function named type() in Python. The documentation says that it that returns the reference to the related type-object. When displaying the object, we can see the string like...

There is another built-in function named type() in Python. The documentation says that it that returns the reference to the related type-object. When displaying the object, we can see the string like...

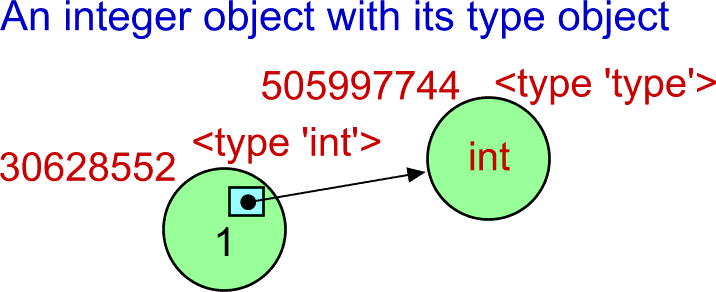

>>> type(1)

<type 'int'>The text speaks for itself. But, hey, "... returns the reference to the related type-object"? Is the type object really separated? If yes, it must be possible to get its identification and type. Let's apply the earlier id() function to the type object:

>>> id(type(1))

505997744LWell, the type objects seems to be separated. (It has its own identification.) Then, what is the type of that type object?

>>> type(type(1))

<type 'type'> Are you confused? If yes, then don't worry. You will get used to. If it is too difficult for you now, think in terms the type is bound to the object that represents the value.

Are you confused? If yes, then don't worry. You will get used to. If it is too difficult for you now, think in terms the type is bound to the object that represents the value.

Some other simple Python objects/types

They are boolean constants, float numbers, complex numbers, and strings. There is also a special type and the constant named None:

>>> id(True)

505930304L

>>> id(False)

505930280L

>>> type(False)

<type 'bool'>

>>> type(1.1)

<type 'float'>

>>> 1+5j

(1+5j)

>>> type(1+5j)

<type 'complex'>

>>> type('some string')

<type 'str'>

>>> None

>>> type(None)

<type 'NoneType'>Values of objects of the simple types can never be changed!

When working with objects in various programming languages, it is usual to think about the object as about a data space bound to some functionality (the methods). It is very usual to think about them as about "capsules" that can change their internal state, i.e. change the content of their internal data variables. This is not the case of the simple-type Python objects.

Any Python object of a simple type cannot change its value! Once the object was created, it stores its initial value until the object is destroyed. In other words, the object shown in the upper examples will always behave as constants. The objects of the simple types represent the captured value. They never (logically) act as a memory space that could be reused for different values. In other words, having reference value to some simple object, you can be sure that you always get the same value.

This fact may be surprising for many programmer, and it brings a whole lot of questions. The true beginners just do not care. Actually, is it that unnatural? When working with the symbol 1 (one) in mathematics, you would never expect that the same symbol changed its internal value to 5.

There are reasons for the "strange decisions" of the authors of Python. The reasons may not be immediately apparent. One of the reasons is that the simple-type objects are to be shared heavily, because assigning the value means actually assigning the reference to the object. It will be more apparent later.

There are also consequences of the constant nature of the objects of the simple types. The consequences could be quite disturbing at first. For example, ignoring the fact may lead to the very inefficient string processing in the sense of time/space complexity of operations.

Built-in containers

The more-complex built-in types of objects are lists, tuples, dictionaries, and sets. They are designed to contain other objects. Because of that we call them containers (as it is usual also in other programming languages).

A list allows you to store and update a sequence of other objects (the order is preserved). Tuple-type objecs are similar to lists, but they cannot be modified after creation. A dictionary stores pairs key, value where the key is used to access the value part (i.e. associative access; also known as a map or a hash table). A set allows you to capture a set of objects. Sets can be tested, modified and otherwise manipulated using operations that are known from the set theory (mathematics).

It is extremely important for understanding how Python works, that all container objects always contain only the references to the objects representing the values.

Tuples and lists

Tuples came from mathematics. They contain certain number of elements in some order. A single tuple in Python can contain elements of more types.

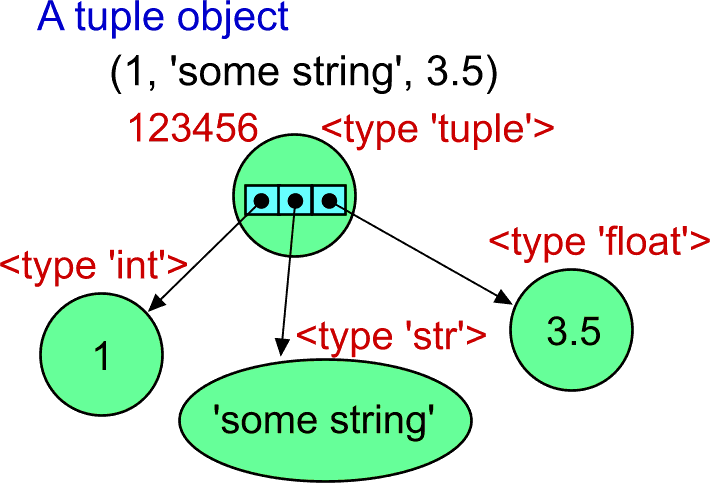

>>> t = (1, 'some string', 3.5)

>>> t

(1, 'some string', 3.5)Now, how should we imagine the tuple object? How it looks inside?

Surprised? The tuple object does not contain the elements inside. The element objects are located outside, and they are bound to the tuple object only via refrences. The value part of the tuple object from the example is actually only the array of three references. In other words, a tuple stores the array of references of fixed size. It means that the tuple object with three elements has always the same memory footprint -- it uses the same amount of memory independently on how big are the element objects.

Surprised? The tuple object does not contain the elements inside. The element objects are located outside, and they are bound to the tuple object only via refrences. The value part of the tuple object from the example is actually only the array of three references. In other words, a tuple stores the array of references of fixed size. It means that the tuple object with three elements has always the same memory footprint -- it uses the same amount of memory independently on how big are the element objects.

References in Python are always untyped -- they are references to any type. This means that the element of a tuple can be the object of any type/class.

There is one important thing to be mentioned. The tuple object cannot be changed after it was created. This means that its value is constant. What does it really mean? The static array of references cannot be changed. If the refered element objects are also constant, then the logical value of the tuple remains the same "forever".

What about lists?

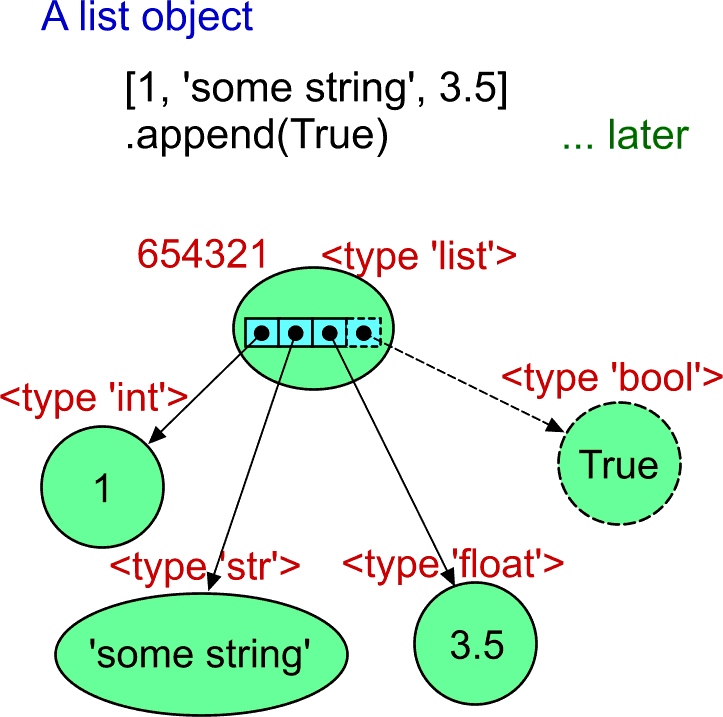

>>> lst = [1, 'some string', 3.5]

>>> lst

[1, 'some string', 3.5]How can we imagine the list object?

The list object is very similar to the tuple objects. But there is one significant difference. The array of references (that act as the value of the object) is a dynamic array. It can change the number of elements. Being capable of growing and/or shrinking, it also means that it makes also sense to be able to change the value of the existing references (to assign another reference value). This means that the list object with the given identity can change completely during its lifetime.

The list object is very similar to the tuple objects. But there is one significant difference. The array of references (that act as the value of the object) is a dynamic array. It can change the number of elements. Being capable of growing and/or shrinking, it also means that it makes also sense to be able to change the value of the existing references (to assign another reference value). This means that the list object with the given identity can change completely during its lifetime.

So far, I tried to avoid using the variable names. Why? It will be clear at the end of this part. Anyway, it is neccessary to use the variable now for demonstration of the difference between the list and the tuple. The lst variable was assigned the list object. The same variable can be used later to call the append() method of the object. The list object gets one more element (it becomes bigger; see the dashed-line parts of the above image).

>>> lst = [1, 'some string', 3.5]

>>> lst

[1, 'some string', 3.5]

>>> lst.append(True)

>>> lst

[1, 'some string', 3.5, True]When trying to do the same with the tuple object...

>>> t = (1, 'some string', 3.5)

>>> t

(1, 'some string', 3.5)

>>> t.append(True)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'tuple' object has no attribute 'append'... not only that the tuple class does not define the append() method, but there is also no other way to modify the tuple. You can think about the tuple object as about some frozen list. The references inside the object cannot be assigned. Also, the array of the references cannot grow. There will always be three and only the three references inside, in this case.

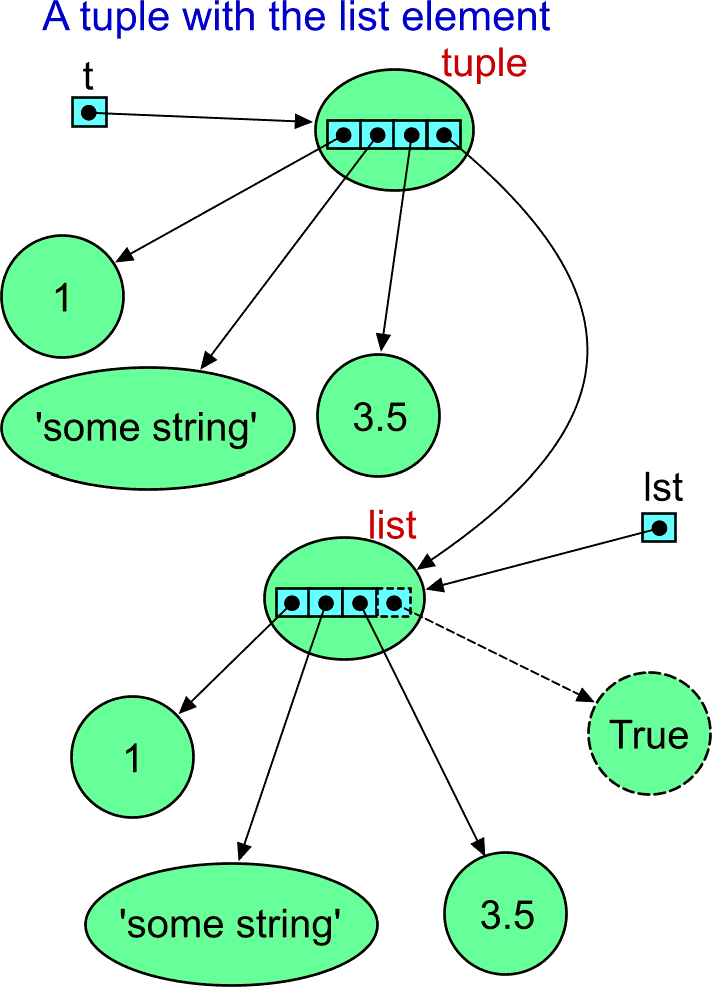

I know I am repeating what was said above. But we have to be careful what does it mean. The same tuple can actualy represent something that changes! Let's use the list as another element of the tuple. Of course, the list object has to be created first. (Note: I have to use the named variables again even though they will be explained later. They will be drawn as separated references with the name on the image. From now on, I am also going to use simplified visualization of the type information of the objects if it is apparent.)

>>> lst = [1, 'some string', 3.5]

>>> lst

[1, 'some string', 3.5]

>>> t = (1, 'some string', 3.5, lst)

>>> t

(1, 'some string', 3.5, [1, 'some string', 3.5])The list object referenced by the lst variable was included as the fourth element of the tuple. (It is a different tuple than in the earlier example. It has four elements now.) But the lst variable is still available, and it can be used to call the method of the referenced list object:

>>> lst.append(True)

>>> lst

[1, 'some string', 3.5, True]The list object changed. What about the tuple that you may consider to be independent on the situation?

[1, 'some string', 3.5, True]

>>> t

(1, 'some string', 3.5, [1, 'some string', 3.5, True])Ooops! The tuple is different now! And they say the tuple cannot be changed! And this is true. The tuple object value did not change because the references in the internal array are the same. However, there is no way to display symbolicaly the list object other than using its representation. The image explains it better:

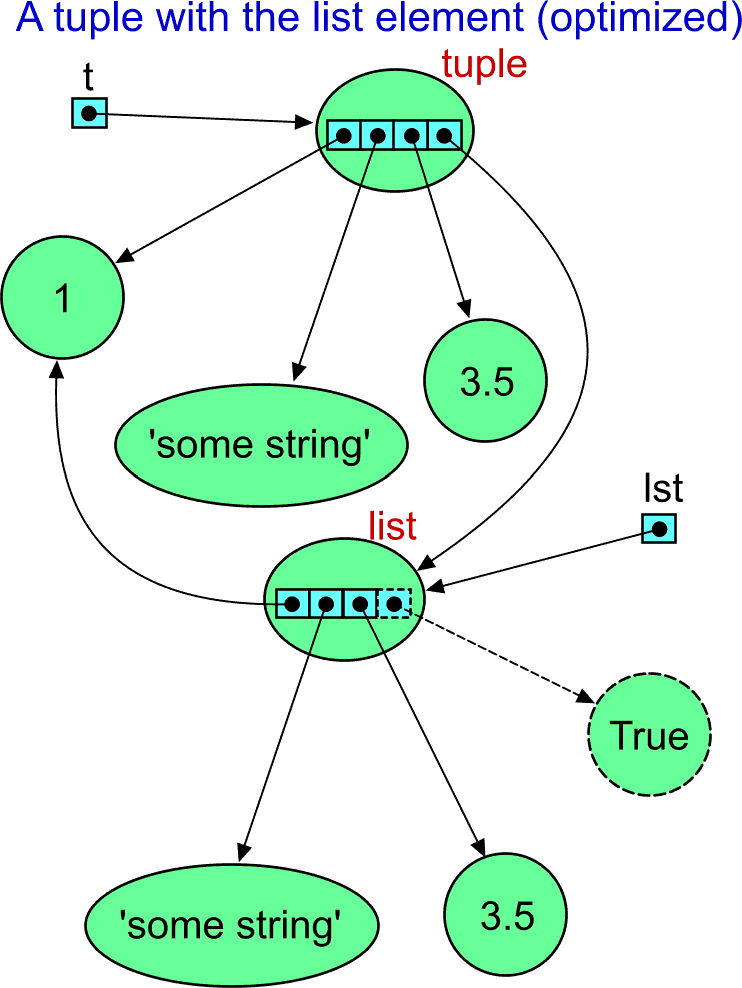

If you payed attention, you may ask: "Where is the sharing of the 1 object?" We can check the identifications (the numbers changed as they are usually different for each run of Python):

If you payed attention, you may ask: "Where is the sharing of the 1 object?" We can check the identifications (the numbers changed as they are usually different for each run of Python):

>>> id(lst[0])

31021656L

>>> id(t[0])

31021656L

>>> id(lst[1])

31160288L

>>> id(t[1])

30854384L

>>> id(lst[2])

31082424L

>>> id(t[2])

31082400LNotice that both the list and the tuple can be indexed (zero based) as if they were arrays. Now you already know why! It comes almost for free in the Python language, because both tuples and lists store the array of references inside. Indexing here means getting the reference from the array on the index. It is automatically dereferenced, and you have the access to the element object.

And yes, the identification of the integer objects from the list and from the tuple are the same. It means that the object is the same, identical. The object is shared even though there is no apparent explicit reason. Recall that it is one of the Python interpreter optimizations. Then the image should look like that:

The most important conclusion so far is that containers always contain references to the objects with the value. They do not store the value explicitly inside itself. The "strange behaviour" usually means that the person who complains is not aware of the usage of references instead of target-object values. Once you know that, you also know the positive consequences. Working with the container of certain size take the same time independently on how complex are the element objects.

The most important conclusion so far is that containers always contain references to the objects with the value. They do not store the value explicitly inside itself. The "strange behaviour" usually means that the person who complains is not aware of the usage of references instead of target-object values. Once you know that, you also know the positive consequences. Working with the container of certain size take the same time independently on how complex are the element objects.

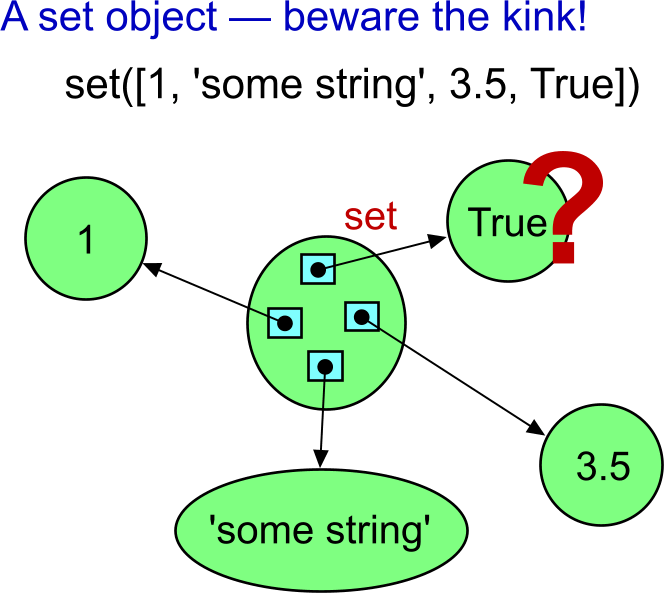

Sets

The documentation says: "A set object is an unordered collection of distinct hashable objects." Unlike a tuple of a list object, a set object does not capture the order of collected elements. Try the following:

>>> mySet = set([1, 'some string', 3.5])

>>> mySet

set(['some string', 1, 3.5])Well, the strange syntax... The set type was added in Python version 2.4, which means quite late. Actually, the above code does not use any special syntax. You can even (re)define the class set that would be used the same way. As we need to pass some initial elements when the object is created, we need some other container that contains them. The authors of Python prefer a list. However, you can pass also other iterable objects. Try it with the tuple:

>>> set( (1, 'some string', 3.5) )

set(['some string', 1, 3.5])As for other types, if possible, the representation of the object has the form that could be copy/pasted to a source file to get the object with the same content. Even though we passed a tuple, the representation shows the list as the argument. This is because there is no captured knowledge what was passed to the constructor. Notice also that the order of the elements in the sequence has changed. This is because the set object does not caputre the initial order of elements either.

Newer versions of Python support also the new syntax for creation of a set object it uses curly braces -- as usual in mathematics. There is one exception. The empty set cannot be expressed as {} because it is already used for empty dictionary object. We must use set() or set([]) instead:

>>> {1, 'some string', 3.5}

set([3.5, 'some string', 1])

>>> set()

set([])

>>> type(set())

<type 'set'>

>>> {}

{}

>>> type({})

<type 'dict'>"OK! Now I know how Python set work internally!" Well, there are some kinks that you would not expect. You may want to create the set like this:

"No problem!"

"No problem!"

>>> set([1, 'some string', 3.5, True])

set(['some string', 1, 3.5])"Oops! Where is my True?" Well, this may be quite surprising. To explain that behaviour, we have to talk about hash values. Probably the simplest way to demonstrate is to use the built-in function named...

hash()

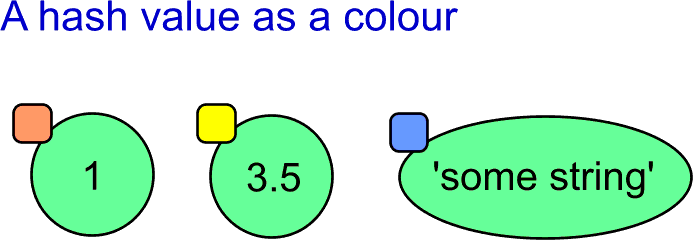

The hash(arg) built-in function returns so called hash value of the passed argument.

Where the name hash came from... Do you now that food made of chopped meat? Even when the resul looks differently than the raw meat, you can still guess that it was made of meat. When you chop some vegetables, the result will look differently. But if you chop another portion of the same kind of meat, the sample will look the same as the other meat sample. You can take only small amount of the result of chopping, and you can still guess if it belongs to the chopped meat or to the chopped vegetable. You can decide using the small sample, even though the samples differ from the originals.

The hash() function does the same with the object passed as the argument. The sample has the form of an integer number. When you get the same number, the source was somehow ekvivalent. Try:

>>> hash(1)

1

>>> hash('some string')

-604248944

>>> hash(3.5)

1879113728You can see that it always return some integer value. However, not every object is hashable. Try:

>>> hash([1, 2, 3])

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: unhashable type: 'list'In this case, the list is not hashable because it can change its content. This means that the next time the object would return a different hash number. Because of this, the concrete hash number cannot always represent the content of the content of the list object.

I will use the small square with a distinct colour to show the value of the hash of the object.

Now back to the set type. The set always contains one value only once. In other words, it contains unique values. On the other hand, the set in Python can be used as a container for objects of different types. We need some general mean to decide whether the object is inside the set or not. Here comes the hash value of the object.

Now back to the set type. The set always contains one value only once. In other words, it contains unique values. On the other hand, the set in Python can be used as a container for objects of different types. We need some general mean to decide whether the object is inside the set or not. Here comes the hash value of the object.

When testing whether the object is inside the set or not, we calculate hash(obj) first. Then we can check, whether the object with the same hash value is inside. The hash function has also one important feature. It can be easily transformed to the index of an array element. When being lucky, the element contains information about the object with the same hash value. When being not so lucky, there is a conflict (two hash values converted to the same index). The conflict must be resolved by some additional mechanism. You can find the reference to more detailed article below in the section describing dictionaries. The internal array must be bigger than the number of elements to minimize the conflicts.

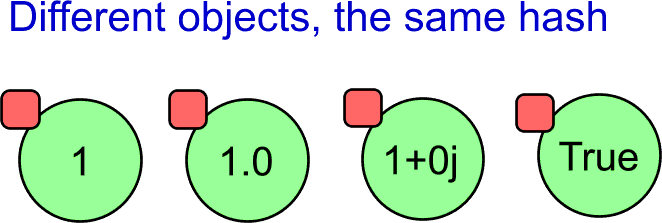

However, there is one kink with Python hash values. Sometimes, different objects may have the same hash value:

However, there is one kink with Python hash values. Sometimes, different objects may have the same hash value:

>>> hash(1)

1

>>> hash(1.0)

1

>>> hash(1+0j)

1

>>> hash(True)

1 This is the reason, why the True was not inserted into the set in the earlier example. When searching for the index in the internal array, the hash value of the True object was already found at the index. The insertion algorithm decides only based on the hash value, even though the object present in the set represents the 1 (of the integer type). Because of that simplification, Python interpreter decided not to insert object with the same value again. There are always some tradeoffs when you look deep enough. Everywhere.

This is the reason, why the True was not inserted into the set in the earlier example. When searching for the index in the internal array, the hash value of the True object was already found at the index. The insertion algorithm decides only based on the hash value, even though the object present in the set represents the 1 (of the integer type). Because of that simplification, Python interpreter decided not to insert object with the same value again. There are always some tradeoffs when you look deep enough. Everywhere.

A final note related to hashability. An object of the same type can be sometimes hashable and sometimes not. For example a tuple object:

>>> type( (1, 'some string', 3.5) )

<type 'tuple'>

>>> hash( (1, 'some string', 3.5) )

1562160248

>>> type( (1, 'some string', 3.5, []) )

<type 'tuple'>

>>> hash( (1, 'some string', 3.5, []) )

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: unhashable type: 'list'If the tuple contains only hashable items, then the whole tuple is hashable. This means that we can get the number that can be used as a signature of the object. However, when the tuple contains a list, it is not hashable any more. This is because the content of the list object can be modified, and there is no fixed number that could represent the tuple content.

Mutable and immutable... What does it mean?

When reading the Python documentation or articles, you will definitely find the terms mutable or immutable. Fancy words, simple meaning. A mutable object can be changed (its content) during lifetime. An immutable object cannot change its content after it was created. In other words, immutable means with the constant content, mutable means with the content that can be modified. But remember, that the content of the container is the array of references. If the container is immutable (e.g. of the tuple type), then only the references are constant. Some or all of the refered objects may still be mutable.

So, what are the immutable types that we have mentioned so far? All simple built-in types are immutable: integer, float, complex, string. The tuple type is immutable. There is also the immutable version of the set type. The type is called frozenset.

Why so much about hashability and mutability? We will use that term later. There is one type heavily used in Python as another type that is based on hashing. The type is named dict.

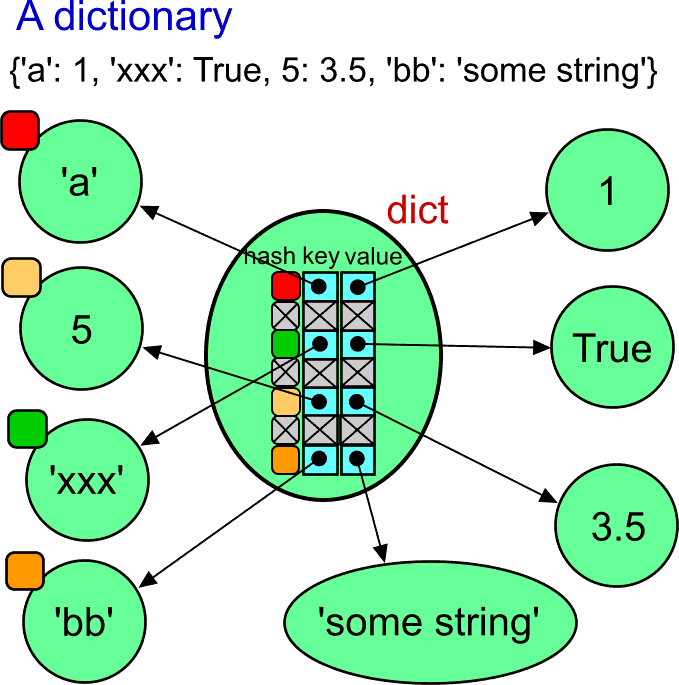

Dictionaries

Dictionary type is one of the major data types in Python. It must be implemented very efficiently not only because you want to use it, but also because the Python interpreter uses it even when you are not looking.

What the doc says about the dictionary type...

As for the mentioned numeric types for keys, we already know why it is so. This is because the hash value of the keys plays the role when accessing the items of a dictionary. If you understand the above set type, it will not be difficult to understand the dict type for you.

A mapping object maps hashable values to arbitrary objects. Mappings are mutable objects. There is currently only one standard mapping type, the dictionary. []...]

A dictionary’s keys are almost arbitrary values. Values that are not hashable []...] may not be used as keys. Numeric types used for keys obey the normal rules for numeric comparison: if two numbers compare equal (such as 1 and 1.0) then they can be used interchangeably to index the same dictionary entry.

>>> dict()

{}

>>> {}

{}

>>> type({})

<type 'dict'>

>>> type(dict())

<type 'dict'>A dictionary object can be created the same way as any other object -- via calling the class name as if it were a function (see the dict()). (You may prefer to name this as "using the class constructor", but there area some differences in Python, and it does not define the term constructor explicitly.

However, there is also a special syntax for creating a dictionary object in Python. It uses curly braces. Using empty curly braces mean creating an empty dictionary. (A side note: This works in Python from early days. Do you remember the new syntax for creating the set objects? Here is the reason why the empty set cannot be created this way.)

Usually, dictionary objects are created and initialized using the special syntax with curly braces. In some cases, we need to prescribe the content of the dictionary explicitly in the source code.

>>> {'a': 1, 'bb': 'some string', 5: 3.5, 'xxx': True}

{'a': 1, 'xxx': True, 5: 3.5, 'bb': 'some string'}Notice that the representation of the just created dictionary has the same form. Notice where the spaces are placed and where they are not. This may be a minor issue. Still, keeping the style helps to make your programs more readable. If you get used to, you will also more easily swallow the sources written by the others.

Notice also, that the representation of the above dictionary content shows the items in a different order. The reason is the same as in the set type. A dictionary organizes the items inside differently than say a list type. There is no way to get the original order.

Sometimes we get data from other sources in another form, and we want to fill the dictionary with them. The following example show the list of tuples that is used for initialization:

>>> dict([('a', 1), ('bb', 'some string'), (5, 3.5), ('xxx', True)])

{'a': 1, 'xxx': True, 5: 3.5, 'bb': 'some string'}The dict() constructor is capable to consume whatever sequence of tuples. This means that it can be a tuple of tuples instead of the list of tuples. It can also be set of tuples. The rule is that the dictionary initialize have to be able iterate through the items and then the item must contain two ordered elements -- the key and the value:

>>> dict( (('a', 1), ('bb', 'some string'), (5, 3.5), ('xxx', True)) )

{'a': 1, 'xxx': True, 5: 3.5, 'bb': 'some string'}Notice a kind of strange example that shows a tuple of strings with two characters. It also meets the rules. The two-char string is split to two chars. The first one is used as the key, the other as the value. (But this is purely for illustration of how it works. Do not search for any meaningful usage of the case.)

>>> dict( ('aA', 'bB', 'cC') )

{'a': 'A', 'c': 'C', 'b': 'B'}A dictionary works as an associative array. Therefore the syntax directly reflects the idea. You can use a key value as if it was an index. You can read the existing value, and you can assign both the existing item (i.e. modification) or the new item (i.e. creation). We can also delete an element using the del statement. (We need the variable name for that. The variables will be explained a bit later, as said earlier.)

>>> d = {'a': 1, 'bb': 'some string', 5: 3.5, 'xxx': True}

>>> d['a']

1

>>> d['bb']

'some string'

>>> d[5]

3.5

>>> d['xxx']

True

>>> d[0]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

KeyError: 0

>>> d[0] = 'new string'

>>> d[0]

'new string'

>>> d

{'a': 1, 0: 'new string', 'xxx': True, 5: 3.5, 'bb': 'some string'}

>>> del d[0]

>>> d

{'a': 1, 'xxx': True, 5: 3.5, 'bb': 'some string'}Dictionary illustrated

The time has come to have a look inside.

There is plenty of objects here. However, keep in mind that the dictionary contains only references to them. Whatever you do with the dictionary, you modify only the internal array of references.

There is plenty of objects here. However, keep in mind that the dictionary contains only references to them. Whatever you do with the dictionary, you modify only the internal array of references.

When searching associatively for a value, the hash value of the key is calculated. The hash value is transformed into the index to the internal hash table. If there is no conflict, you get the reference to the value object very quickly.

The hash value of the value object does not play any role. Therefore, it is not illustrated at the value objects. Actually, the value object need not to be hashable and it may not be possible to calculate their hash value. For example, the value object could be a list or a dictionary.

If you are interested in implementation of dictionaries, you can find more detais at http://www.laurentluce.com

Variables

Now it comes. What really are the variables in Python? Variables in Python are named references. The name is stored in memory during runtime. It is not lost during compilation as in classical compiled languages. A Python variable has no type associated to the name (unlike in compiled languages). This is because a Python variable stores always the same type of value. It stores a reference to the target object.

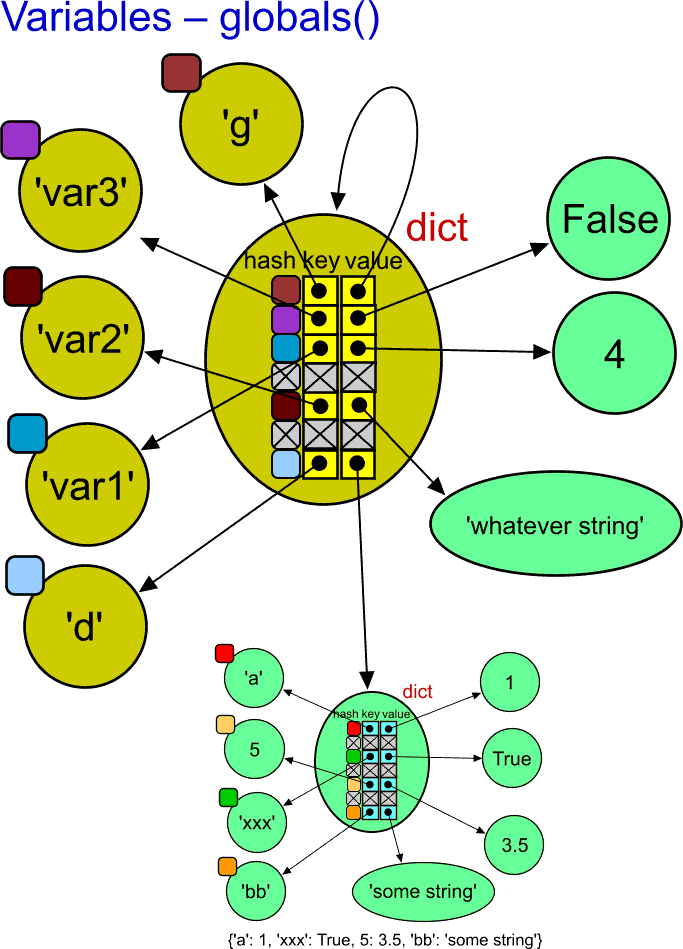

And how the names and the references are bound together. You may have already guessed. The variable names are keys to a hidden dictionary (used by the Python interpreter for the purpose). The references to the targets are at the value side of that dictionary.

Actually, the hidden dictionaries are not that hidden. There are functions that gives you the access to the dictionaries. One of them is the built-in function named globals().

Start the Python interpreter in interactive mode from scratch and try the following:

Python 2.7.1 (r271:86832, Nov 27 2010, 17:19:03) [MSC v.1500 64 bit (AMD64)] on win32

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> d = {'a': 1, 'bb': 'some string', 5: 3.5, 'xxx': True}

>>> d

{'a': 1, 'xxx': True, 5: 3.5, 'bb': 'some string'}

>>> var1 = 4

>>> var2 = 'whatever string'

>>> var3 = False

>>> g = globals()

>>> type(g)

<type 'dict'>

>>> g

{'var1': 4,

'd': {'a': 1, 'xxx': True, 5: 3.5, 'bb': 'some string'},

'var3': False,

'var2': 'whatever string',

'__builtins__': <module '__builtin__' (built-in)>,

'__package__': None,

'g': {...},

'__name__': '__main__',

'__doc__': None}Notice the last variable named g, that was assigned the result of the globals(). Next, we have tried it is of the dict type. In other words, it is a normal dictionary, indistinguishable from other dictionary objects. When displaying its representation, we can see all the defined variables inside, plus some more. (The dictionary representation was manually formatted to make the dictionary items more visible.)

Notice that even the g name is inside. But its value cannot be easily represented as it points to itself. Let's illustrate it!

The reason for using the dark yellow colour of the object is to emphasize that they were created by the Python interpreter for its internal purpose. Otherwise, the object are quite normal objects of their type.

The reason for using the dark yellow colour of the object is to emphasize that they were created by the Python interpreter for its internal purpose. Otherwise, the object are quite normal objects of their type.

There are some restictions for identifiers in any programming language. They usually must be compound of letters, numerals, and some special characters (e.g. undercore). To make it short, the keys in the hidden dictionary must be of the string type.

Assignment operation

Now it should be clear that the assignment to a variable means that the string form of its name is or found in the appropriate internal dictionary as a key, or the item for the key is created. The assigned value is always some object. The reference to the object is used as the value part of the dictionary.

More variables

What about the dirty idea to create dynamically a variable that was not given its identifier in the source code. Say, its name could be dynamically created, read from a text file or whatever. Here we simulate it by assigning the s variable.

>>> s = 'myVariable'

>>> g[s] = 12345

>>> g

{'var1': 1,

'd': {'a': 1, 'xxx': True, 5: 3.5, 'bb': 'some string'},

'var3': False,

'var2': 'whatever string',

'__builtins__': <module '__builtin__' (built-in)>,

'__package__': None,

'myVariable': 12345,

'g': {...},

's': 'myVariable',

'__name__': '__main__',

'__doc__': None}See, the myVariable with the content 12345 is there! Can we use the newly created variable name as if it was defined in the source text?

>>> myVariable

12345It works! Notice that it is very different in programming languages to write an identifier and write a string literal with the same name inside.

Warning: the globals() name suggests that it stores global variables. However, the dictionary stores only top-level variables inside a module. There is that many of such dictionaries, how many modules is used in your program. There also is the built-in locals() function that returns the dictionary of local variables. However, you should never modify it.

The above illustration shows how variables are implemented in Python. However, it looks quite complex on its own. To simplify the illustration of used variables, I will use pictures like the following. It illustrates the same case -- except the g variable.

Some final notes

"And why you see it changing not--

And why so strange are strings."

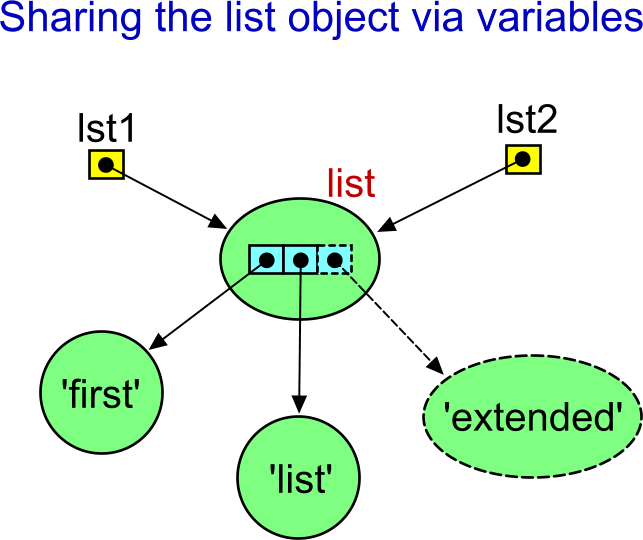

"Oh, now I know! Assigning a variable means sharing the object via another reference..."

>>> lst1 = ['first', 'list']

>>> lst2 = lst1

>>> lst1

['first', 'list']

>>> lst2

['first', 'list']

>>> lst2.append('extended')

>>> lst2

['first', 'list', 'extended']

>>> lst1

['first', 'list', 'extended'] "Oh, yes. I have told you!" What about this?

"Oh, yes. I have told you!" What about this?

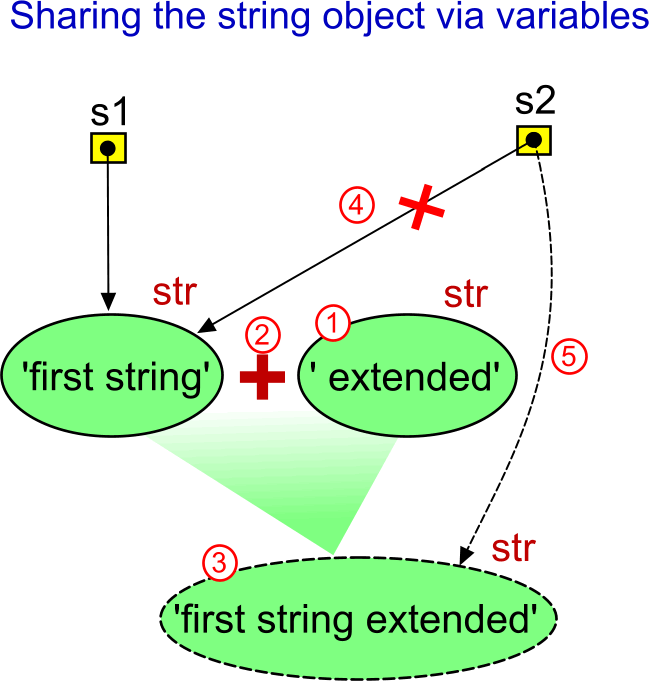

>>> s1 = 'first string'

>>> s2 = s1

>>> s1

'first string'

>>> s2

'first string'

>>> s2 = s2 + ' extended'

>>> s2

'first string extended'

>>> s1

'first string'Why the list object behaves as expected (when knowing we work via references), and why the string behaves so strangely? Is there any exception? Do string variables also use references to the string object? Aren't they implemented somehow differently?

I hope it is the "Aha!" problem for you. The key difference is that the list objects are mutable. This means that the .append() method is able to modify the same object. However, strings are immutable. The concatenation operator (+) cannot modify the original string object. The string object with the value ' extended' must be created first, then the + operator puts the values of the two strings together and creates another string object. Only after that the s2 variable is assigned the reference to the newly created object. Therefore the s1 and s2 cannot point to the same object. (The string object with the value ' extended' exists only temporarily. It is not referenced later, and it will be destroyed by the garbage collector.)

I hope it is the "Aha!" problem for you. The key difference is that the list objects are mutable. This means that the .append() method is able to modify the same object. However, strings are immutable. The concatenation operator (+) cannot modify the original string object. The string object with the value ' extended' must be created first, then the + operator puts the values of the two strings together and creates another string object. Only after that the s2 variable is assigned the reference to the newly created object. Therefore the s1 and s2 cannot point to the same object. (The string object with the value ' extended' exists only temporarily. It is not referenced later, and it will be destroyed by the garbage collector.)

If you want to learn more about implementation of strings, see

http://www.laurentluce.com

(The end of the part 3)

--------------------------

Part 4 will reflect your questions...

+ some consequences of the above,

+ user defined classes.

Have a question about something in this article? You can receive help directly from the article author. Sign up for a free trial to get started.

Comments (0)